Luck and talent have accounted for many success stories separately, but, in the case of naval architect Jack Hargrave, they both played a role. Lucky to be in the right place at the right time, Hargrave also had the innate talent that allowed him to capitalize on that luck.

Hargrave’s design clients read like a Who’s Who of the marine industry: Hatteras, Burger, Cheoy Lee, Trumpy, Palmer Johnson, Huckins, Stephens, Derecktor, deVries Lentsch, Striker, Amels, and dozens of others. As his designs were built and moved into the waterways, they became advertisements for his services that garnered more and more calls.

Hargrave was comfortable doing custom megayachts with cost-is-no-object budgets, but he also had a clear understanding of how to make a production boat cost effective. The result was a spot at the top of American powerboat design for more than three decades.

Growing up on the upper peninsula of Michigan, Jack Hargrave was molded by an energetic father who, after a variety of jobs, wound up in the boating business. Hargrave’s childhood was the dream of any Boy Scout: hiking, camping, and sailing in the wilderness. But he was attracted at an early age to art and drawing, and this set the stage for his later career.

As a boy, Hargrave sold drawings around his neighborhood for a penny each. Years later, when his yacht-design business was booming, a friend visiting his mother remembered his childhood sales and asked what he was doing now. “Oh,” said his mother, “he’s still selling drawings.”

It’s been said that Jack Hargrave had a good eye when it came to making a yacht look right, and that was literally true: A boyhood archery accident left him blind in one eye, a disability that kept him from military service during World War II, but never affected his design sense.

Since Hargrave wasn’t able to join the Navy or the Coast Guard, he spent the war years aboard merchant ships. Afterwards, he returned to Duluth, where his father had a marina and, for several years, he skippered both sail and motoryachts on the Great Lakes in the summer and in Florida in the winter. He married his wife, Janet, during that time, but she had to get her boat operator’s license before he would tie the knot.

By the early ’50s, with a daughter starting school and another child on the way, he worried that being a yacht captain wasn’t a good way to support his family. He took a job as the project manager for an avid fisherman who was having a 33-footer built in Peru to fish the Humboldt Current. Intrigued by the design proccess, he took some textbooks with him and spent evenings wading through the heavy tomes of naval architecture: Skene and Froude and others.

It’s said that luck is just preparation meeting opportunity and it was at this point that Hargrave laid his groundwork. He badgered Westlawn Institute of Marine Technology, a correspondence school in yacht design, to send him the entire course at once, rather than enduring postal delays for each installment. He used his time in Peru to power through the course, earning a 100-percent score on his graduation exercise, which, in fact, was a boat design he’d done before he started his studies.

At that time, a degree in yacht design from Westlawn and a dime would barely buy a cup of coffee: Naval architecture schools such as Stevens, Webb, and the University of Michigan looked down their haughty noses at Westlawn grads.

Hargrave set up his own boatbuilding company in West Palm Beach, Florida, but lasted just long enough to learn that it was a tough business. This led to his first turn of luck: The premier builder of sportfishing boats, John Rybovich, offered young Hargrave a job.

At Rybovich, he learned the practical side that his book learning hadn’t taught him: How to create a boat that was both an artistic and a financial success. In later years, Hargrave credited Rybovich with being one of the two men who led to his success and, during his days there, he would meet the second.

Charlie Johnson was an ardent fisherman who, with a string of successful auto dealerships, could indulge his passion. He was also Rybovich’s best customer, having built five boats there.

At one point, Charlie Johnson saw some preliminary drawings that Hargrave had done for an 85-foot motoryacht while teaching himself yacht design, and found the drawings appealing. When it was time to build a bigger boat, Johnson gave Hargrave the job of designing it.

Admitting later that he had never before done a full set of drawings for any boat larger than 30 feet, Hargrave spent a family vacation worrying about how to design the support for a stern bearing. He completed the project, which was built by Burger Boat Company in steel. The launching of the 90-foot Seven Seas was also the launching of Jack Hargrave.

Coincidentally, Seven Seas was also the first build for Henry E. Burger, the grandson of the yard’s founder and, having started their careers together, Burger and Hargrave would join forces on many future boats.

Most important, however, was that his first design commission allowed Jack Hargrave to hang out his own shingle in 1958. With a reputation from Seven Seas for large-yacht design and steady work from a gracious John Rybovich, Hargrave’s Palm Beach office flourished.

Johnson showed up at Hargrave’s door a year later with a successful sock manufacturer named Willis Slane in tow. Johnson and Slane and other members of the Hatteras Marlin Club in North Carolina got the idea to build a fiberglass sportfishing boat that could handle the rugged waters of the open Atlantic. Though he’d talked to other designers about the project, Slane was impressed by Hargrave’s no-nonsense approach. When Hargrave showed a sketch of a 39-footer, Slane signed a letter of intent for a $2,000 design fee. Hatteras Yachts was born, with J.B. Hargrave as designer.

When the drawings were done, Slane gave the Hatteras team, working in a rented auto garage, just four months to create the molds and build the boat. Fiberglass was unproven so Jack Hargrave had Hatteras build sample panels and he drove over them with his Corvair to test their strength. Said one of the team of furniture-makers-turned-boatbuilders, “We went on and built that first boat because we didn’t know we couldn’t do it.”

When Slane promoted that first Hargrave-designed Hatteras sportfisherman, he coined a term that has since entered the nautical lexicon: “convertible.” Because the boat had a furniture-quality interior-the factory at High Point, North Carolina, was in the heart of America’s furniture industry-Slane wanted buyers to know that this boat would be as good at cruising as it was at fishing, hence it was convertible.

The first Hatteras, a 41-footer, was launched in early 1960 and stayed in continuous production for 11 years, with 745 boats built, only to be replaced by the Hatteras 42, also a Hargrave design.

| | |

If Seven Seas was the yacht that launched Jack Hargrave, then it was Hatteras Yachts that made J.B. Hargrave a household name in yachting. Hargrave went on to design most of the Hatteras yachts for three decades (including the 53-foot motoryacht that sold more than 600 hulls) and had an all-new series of motoryachts from 84 to 100 feet under construction at Hatteras. It was a phenomenal run that has never been equaled: one designer, one builder, three decades, and scores of successful yacht designs.

Hargrave’s firm continued to prosper, with Hatteras and Burger remaining the largest clients, and the Hargrave office moved from ritzy Palm Beach across the Intracoastal Waterway to downtown West Palm Beach to provide space for the growing staff.

Charlie Johnson wasn’t done with Jack Hargrave, though, and he returned in 1963 with a challenge: Design a boat to break the Miami-to-New York speed record. Hargrave came up with a 37-foot sportfisherman-complete with flying bridge-that Johnson built at his Daytona Marina and Boat Works and, powered with his turbocharged 380-horsepower Daytona engines, the boat knocked nine hours off the previous record.

Johnson wasn’t content to rest on his laurels, however, and commissioned Hargrave to build an even faster boat. The result was TX-41, a 41-footer with a long foredeck and a big cockpit. Powered by four Daytona engines to a speed of more than 60 mph, TX-41 knocked an amazing 15 hours off the record Johnson had set just 11 months earlier. It also proved to be such a good sea boat that several twin-engine production versions with enclosed cabins were built for sportfishing.

But in spite of that offshore racing success, Jack Hargrave complained he was being typecast. His style was conservative, and many of his earliest designs still have an ageless elegance derived from a sweetly curving sheer line and a classic sensibility about where the superstructure should rest on the hull. His yachts kept pace with design trends, though they were never extreme. He had a versatility rarely found in modern designers and was just as comfortable designing a 160-foot ketch-rigged sailing yacht as he was with the unpretentious but nicely proportioned Prairie 29 coastal cruiser. Decades before anyone ever thought of the terms “shadow yacht” or “support yacht,” Jack Hargrave had designed the 120-foot Buckpasser, a helicopter-equipped mothership for a sportfishing enthusiast.

The Hargrave office also produced a wide variety of passenger and cruise vessels, ranging from a fleet of Michigan-based high speed aluminum fast ferries to the famed harbor cruise vessel, Jungle Queen, a fixture on the Ft. Lauderdale waterways for more than three decades.

| | |

In the early ’70s, Hargrave dipped his design pen into big-ship waters with an innovative catamaran tug and barge system. Dudley Dawson, Yachting’s Technical Editor and a naval architect in his own right, joined Hargrave’s design team in 1974 to work on this 625-foot tanker. The finished design was patented and two “catugs” were built initially: one to carry petroleum products and the other with tankage for a variety of chemical products. Eventually, an additional 18 ships were built from Hargrave’s patented concept.

Over the years, Jack Hargrave set a number of milestones for design. The 125-foot Arara III claimed three records: largest modern American yacht, largest Burger, and largest all-aluminum yacht in the world when she was launched in 1977 (see “Double Burger with Everything,” July 2008). He designed the largest sightseeing boat in Canada at 116 feet and 600 passengers, and turned around to create a private 65-foot riverboat-style sternwheeler complete with Hargravedesigned steam engines and steam-powered air conditioning. In the late ’80s, the Hatteras custom yachts (up to 130 feet) were the largest fiberglass production yachts in the world.

Jack Hargrave was a complicated man, who kept his distance from both his design team and clients. With his ramrod posture and signature crewcut, Hargrave wasn’t someone you invited to share a beer after work. Yet his employees recall that he insisted on two cookie breaks each day, when his team relaxed with Oreos.

To put his achievements in perspective, remember that most of his designs were done before the days of computers and design software. Hargrave and his team used traditional drafting tools such as curves and splines, sheets of transparent vellum, and sliderules to handle the complex engineering formulas.

“Jack was a good listener,” recalls Dawson. “At some point during initial client meetings, he’d pull out a sheet of paper and a number two pencil and start sketching. By the end of the meeting he’d have a profile, and it was so good you could take a quarter-inch scale and pull a dimension off it. The first few times I saw him do this, it stunned me. And, of course, it stunned the client! They would say, ‘Can I have a copy?’ and Jack would reach for the design and say, ‘No, but we can draw you up a contract.’ There was a businessman sitting inside all that talent.”

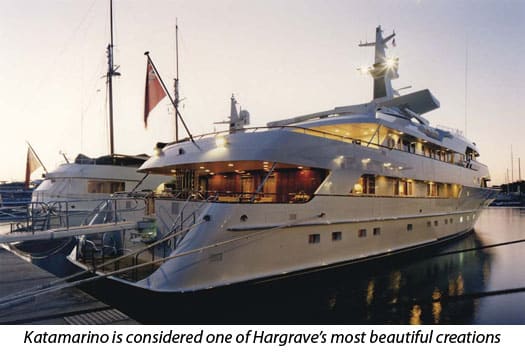

In 1991, Hargrave designed his largest yacht and one that has been called his most beautiful: the 184-foot Katamarino built by Amels. After a minor stroke, he scaled back his staff and took only clients or projects that he enjoyed. He claimed he was in “semi-retirement” because he no longer worked Sunday afternoons.

| | |

In 1995, he announced a collaboration with Tripp Design, known for its sailboat designs, and he was excited about the opportunities on the wind-powered front. But it was not to be, as Hargrave passed away in his sleep in early 1996. An era was over. Or so it seemed.

Mike Joyce, who first worked with Jack Hargrave as a broker and later collaborated on several Cheoy Lee projects, had started researching the biography of the designer before his death. Afterwards, the Hargrave family encouraged him to continue it and, in the process, he heard they were getting offers to sell the design office.

Hargrave’s secretary, Barbara Bishop, suggested Joyce speak with the family. “I became convinced that I was supposed to buy Jack’s business, as preposterous as that sounded even to me,” Joyce said.

Joyce convinced the family that the Hargrave name was an icon in the industry and, by using it to launch a company to build highquality yachts, it would continue to play a role in the marine business into the future. Joyce was proven right-the Hargrave name remains a major contender in the world of large yachts.