Equipped For Adventure

In the best sea stories, there’s a tiny ship in the clutches of peril. Some of these tales are resolved with outside help from the U.S. Coast Guard or commercial salvors 200 miles offshore, or beyond where international military and Amver merchant ship assistance adds another layer of aid. But the best stories are sorted out by the vessel’s own crew. As yachts venture farther, transiting oceans to reach pristine cruising grounds, their crews must rely more on the resources carried aboard.

“Peril” is subjective, too. A dream yacht vacation can be ruined by a failure in one of the innumerable systems aboard, though often no one is in real danger. Try to predict any problem that could have a negative impact on the enjoyment of your yacht.

Jimmy Hone has commanded a dozen or more transoceanic voyages aboard yachts from 130 to 240 feet. He begins trip preparation with key crew. “Everyone has to run their department, even if that department is only one person,” he says. For large yachts, Hone wants an engineer, a mate, a chef, and a chief stewardess aboard at least a month before the trip. Each must plan equipment they’ll need and consider the environment they’ll be in and how it will affect their ability to find solutions. “If the toaster stops working [in the U.S.] I can have 20 new ones that day. In France, Italy, Greece, I can buy 20, but they won’t work on the boat.”

Smaller yachts with fewer crew rely more on yards and mechanics, but the goal is the same. Hone wants all equipment serviced or repaired and tested, and spare parts inventoried and stowed without burning out his crew. “If the trip starts out as a mess, it’s going to end up a mess,” Hone says. Knowing what he has aboard lets him know the best way to sort out problems.

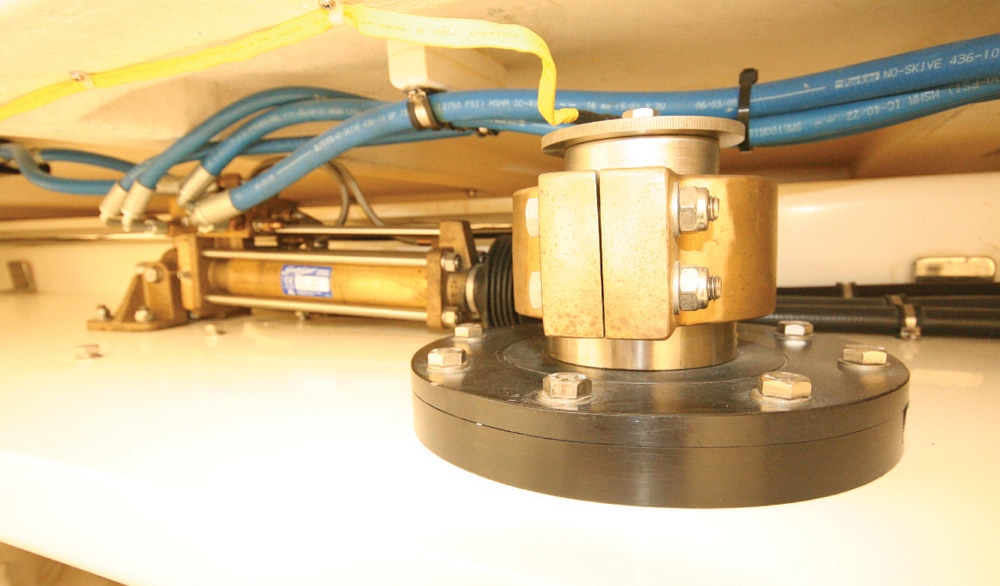

Self-sufficiency means you can repair, bypass, or jury-rig failed equipment, or otherwise work through problems. Even with redundancy, the wrong failure of any one steering component can leave rudders limp or pinned hard to one side. “You’ve got to have some mechanism for getting your rudders centered and locked there,” says Fred Zucker, founder of Seaworthy Services in Palm Beach Gardens (www.oceanalloys.com). He says preassembled hoses allow the crew to bypass a bad cylinder, helm, or pump, which will often return at least limited steering.

Hydraulic hose in the two most common sizes and longer than the longest run aboard can fix any steering, bow thruster, windlass, or even fuel-line failure. No-skive fittings assemble with few tools, and adaptors work with other hose sizes. “With two reels of hose and $300 or $400 worth of steel adaptors, you can fix almost anything,” Zucker says. He also suggests spare steering cylinders and a hydraulic fluid cooler.

An assortment of wire, fittings, fuse holders, and fuses can similarly bypass any circuit aboard. Seawater hose and clamps and a wide array of pipe fittings, adaptors, and bushings allow fewer spares to cover more systems—a spare hydraulic fluid cooler might be used to cool transmission oil. “You have to have the wherewithal to deal with whatever happens,” Zucker says.

Short of fire, collision, or severe weather, Zucker says yachts are most vulnerable where propeller and rudder shafts penetrate hulls. Check integrity of hoses, clamps, and seals, and verify shaft alignment. Ensure the cooling- water flow from engines to shaft seals and through redundant crossover hoses between seals.

Inspect rudder and shaft bearings as well as bow thruster seals. Load-test electric bow thruster batteries and carry spare fuses. “For hydraulic thrusters, I’d carry a spare small electric solenoid,” Zucker says, which operates a larger hydraulic solenoid that’s unlikely to fail. Extra helm controls, switches and relays, and a spare hydraulic pump should be aboard if thrusters are critical, such as when stern-to mooring in the Med.

David Gratton, of Martek in Stuart, Florida (www.martekpb.com) prefers not just redundant electronics, but also independent power sources. “I like to see dedicated batteries under the helm with a separate panel and selector switch,” Gratton says. One chart plotter, a radar, the boat’s best VHF, and running lights would then operate even if the main batteries are lost in flooding or fire. On voyages far from home, he recommends spares of critical systems: a complete navigation PC, autopilot components, and parts for satellite phone, Internet, and television systems. While FedEx can bring these spares to most places in a day, customs officials may add a week.

“Most of this stuff doesn’t require preventive maintenance,” Gratton says. “But that doesn’t mean there aren’t things that should be done.” Check antenna and wire connections, inspect for corrosion, and make sure equipment is mounted securely, since vibration can take its toll. Carry fuses, wire, and electrical terminals, a good multimeter, and jewelers’ screwdrivers.

Consider that a comfortable, well-fed crew is a pleasure to have aboard. Air conditioners and refrigeration benefit from preventive maintenance. “If you do it once a year, it isn’t that expensive,” says Rich Meister, vice president of Gulfstream Marine Air Conditioning and Refrigeration in West Palm Beach. “Anything you spend on repairs you’re going to spend anyway, but it won’t break when you and your wife and your kids are on vacation.” He also warns of restrictions on refrigerants. Gas approved in one country may be illegal in another, meaning simple repairs may require a retrofit. “Take care of the equipment you’ve got,” Meister says.

John Wheatley, owner of Florida Marine Tech in West Palm Beach, takes a different view: “It shouldn’t be different than going fishing at a moment’s notice,” he says, meaning a preventable failure is a failure, whether you’re gone for six months or six hours. “It doesn’t matter if you’re going from Palm Beach to Fort Lauderdale, or down to Venezuela or across to the Med,” Wheatley says. “You should be able to jump aboard and go.”

Wheatley suggests asking a mechanic familiar with the boat to recommend spares and tools, and he encourages clients to learn a few simple repairs. “A knowledgeable owner or crew can help me diagnose some things over the phone. The more they know, the better it is for all,” he says. A good multimeter and tools are essential. “An impeller puller is only about $75. That’s a lot cheaper than flying a mechanic somewhere to change an impeller,” he says. Weight restrictions also make onboard tools important. “If we don’t have to [fly a technician with the extra weight of necessary tools], that’s a big help,” he says.

The best tool is often a satellite phone. “You need a [knowledgeable] resource on shore,” Zucker says. “I may not have an answer, but I have a Rolodex full of the best people in the world to call.”

All told, there’s one piece of advice that prepares you for any voyage: Expect unanticipated problems. It’s how they’re resolved that can turn an unfortunate tale into a continuing adventure.