ytgjan09perfhmp525.jpg

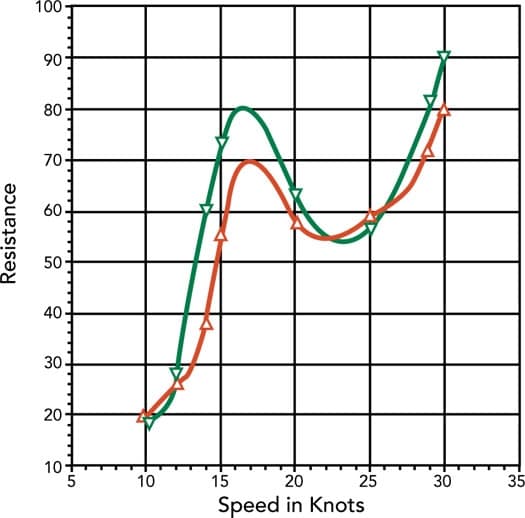

In past columns, I referred to the “hump” region, a range of speeds to avoid when selecting a cruising speed for your boat. I’ve received e-mails from some of you that tell me you’re cruising in that range unknowingly or are stuck there on boats that are underpowered, overweight, or out of trim. The graph on this page, for an 80-foot power catamaran in two different loading conditions, clearly illustrates the problem. The resistance of the boat (which corresponds to required horsepower) peaks at some early point, drops off, and then climbs again.

So, at what speed should you cruise? If you take the left part of the curve (below 12 knots: displacement speed) and right part (above 23 knots: planing speed), it’s easy to imagine a fair line connecting the two, but it’s obviously not the case in reality. There’s a huge hiccup, peaking at about 17 knots: the hump region. This boat requires just about as much power to achieve 17 knots as it takes to run 29 knots. If engines were specified for a top speed of 25 knots instead of 30, it wouldn’t have enough horsepower to “get over the hump,” would never run faster than about 15 knots, and would burn just as much fuel as if it were running 25 knots!

You’ve seen this phenomenon, maybe on a smaller boat, when you’ve added some weight, often by taking on an extra-large load of guests. The boat stood on its transom, roaring at full power and creating a massive wake. It just wouldn’t get on plane until you changed the trim, either with tabs or engine position, and sent everyone forward to flatten out the running angle. That’s when the boat magically sped up and you were able to pull back the throttles and trim out your motor or sterndrive for a comfortable cruise. You just “got over the hump.”

The hump is most clearly defined on the speed/resistance or speed/power curve for your boat, but they aren’t always available. Since power and fuel usage are directly related, you can plot your own curve if you have a FloScan or another way to measure fuel flow. Just keep in mind that if your boat burns the same number of gallons per hour at two or three different speeds, you should run at the highest of those speeds to get the most miles per gallon.

In the absence of a flow meter, the next best thing is to know where your boat’s hump speed starts so you can estimate where the peak lies. The start of the hump is the point where the boat creeps past its “hull speed” and leaves the displacement speed regime. Find it by taking the boat’s waterline length in feet (usually about 90 percent of the boat’s length, not counting pulpit or swim platform), get the square root of that length, and multiply it by 1.34. That’s the hull speed in knots. The peak of the hump speed will usually lie 4 to 6 knots above that.

Here’s how it works for the 80-foot cat. For an overall length of 80 feet, the waterline length will be about 72 feet (80 x 0.90 = 72). The square root of 72 feet is 8.5 (8.5 x 8.5 = 72), and the hull speed is thus 11.4 knots (8.5 x 1.34 = 11.4). Adding 4 to 6 knots puts the peak of the hump at 15.4 to 17.4 knots. A look at the curve shows close agreement with the theoretical numbers. The start of the hump is at 11 knots for one loading condition, 13 knots for the other. The peaks are at 16 and 17 knots.

If the boat is underpowered, overweight, or out of trim, it may be unable to get over the hump. Some boats are sold with base engines that are just enough to plane the boat when it is new, or buyers select power based on their budget. Add a few stores, some options, a dirty hull bottom, or extra guests, and you’ve got trouble. Ask questions before you buy. Look past initial cost and get the upgraded power option.

Overweight is an easier problem to solve: Leave anything unnecessary ashore. If you don’t need full fuel and water, run with your tanks slack. Carry only the gear you need for the planned trip.

An out-of-trim condition, particularly with the stern down, may exaggerate the hump. That’s why “everybody move forward” works for smaller boats. If you try moving weight forward to overcome a hump-speed problem, just make sure you don’t create a dynamicstability problem by over-trimming in the opposite direction.