ytgsep14bottle525.jpg

Back in 1993, I bought an old Bertram 35 from a Ft. Lauderdale repo yard and undertook a top-to-bottom refit of the boat. I hired noted boatbuilder Bill Knowles of Stuart, Florida, to oversee the project and we soon became good friends.

In addition to being a consummately skilled craftsman, Knowles is a noted raconteur and lover of fine wine, and during the ensuing years, I’ve enjoyed many of his fascinating tales of travel, boats, and fishing while we enjoyed a tasty Bordeaux.

One particular story involved a trip to Key West aboard a friend’s boat; on a whim, Knowles wrote a note and stuffed it into a wine bottle that had been drained the previous evening. As the crew set off to return to mainland Florida, he tossed the bottle overboard in the Gulf Stream and forgot about it.

Several years later, he got a call from a woman in Islamorada, only 85 miles up the road from Key West, who had found the bottle bobbing along in the Gulf Stream. But instead of opening the bottle, she placed it on the mantel in her living room where she gazed at it over the years and wondered about the note inside.

“She didn’t want to open it and spoil the surprise,” Knowles said. “It gave her such pleasure looking at that bottle and imagining where it had come from.” One day while cleaning her home, she accidentally knocked the bottle from the mantel and broke it; only then did she contact Knowles. If she was disappointed that the bottle had only traveled a few miles, she never let on.

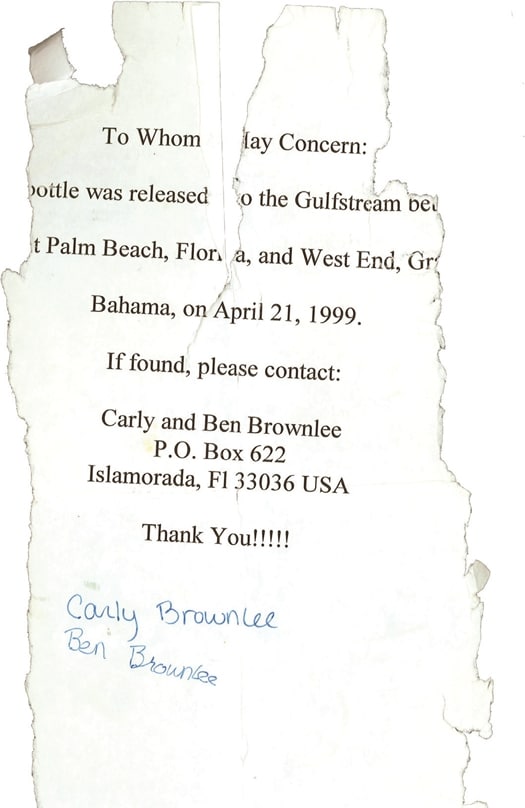

That story stuck with me, and after my Bertram project was complete, my wife Poppy and I decided to try this low-tech form of communication for ourselves. It took us a few years to actually do it, but in 1999 we cobbled up a rudimentary note on our computer, printed out a dozen or so, and stuffed them into empty wine bottles. We then loaded them into a paper grocery sack in anticipation of an upcoming trip from our home in Florida to the Bahamas.

| | |

Our children were still small then, so we put their names on the notes, along with our post office box address. We didn’t think to use e-mail addresses until sometime later. With those early bottles, we obsessed over details like whether we should use packages of desiccant to keep the notes dry, or whether we should seal the corks with candle wax in some pirate-like ceremony. In the end, we did neither-we merely stuffed the notes in, replaced the corks, and flung them out to sea.

As we crossed the Gulf Stream headed east, Poppy tossed a bottle overboard every few miles until they were all gone. We took great pleasure in watching the bottles bob away in our wake and quickly fade from our view, wondering if, when, and where anyone would find them.

It didn’t take long to get the first return: A woman spotted one in Vero Beach, on the east coast of Florida, and wrote to us describing her discovery. The bottle had only been at sea two days and traveled about 100 miles, but hey, a return is a return, and we were ecstatic.

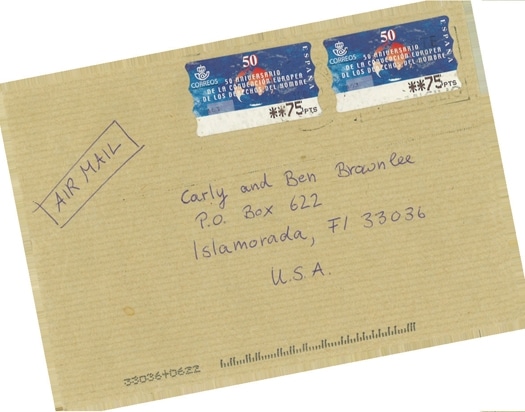

Next came a note from the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and another from Virginia Beach. But it took almost two years before we opened our P.O. box and hit pay dirt-our first international return. A brown airmail envelope covered with foreign-looking stamps sat among the usual bills and junk mail.

| | |

A German woman named Dorle Patzold found one of our 1999 bottles on April 5, 2001, on Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands, off the northwest coast of Africa. While on vacation with her father, Patzold found the bottle on a small beach called Cofete, a brief patch of sand along the otherwise cliff-bound western shore of Fuerteventura. Had the bottle drifted a mile or two in another direction, it would have shattered on the rocks.

We exchanged e-mails with Patzold and she told us of the excitement they experienced while trying to figure out how to open the bottle. They even felt a bit of paranoia, wondering briefly if there might be “poison in the bottle,” or “it might be a bomb.” Eventually reason returned, and after borrowing a construction worker’s hammer, they shattered the glass and read our note, and were happy to find neither poison nor explosives.

Needless to say, Patzold’s letter from Germany and the subsequent exchange of e-mail caused a great deal of excitement in our family, and we had barely gotten through telling everyone who would listen about our amazing new friend, when an even more interesting letter arrived.

In June of 2001, we received a letter from Juan Arnaldo Rodriguez Portelles of Los Angeles, Cuba. He found one of our bottles on a beach in the northeast section of the island on Christmas Eve, 2000, but because he spoke no English, he waited several months for an English-speaking nephew to arrive and translate.

Portelles’s poignant letter tells of his life as a farmer, a life he describes as “a little bit boring.” He spoke of his hobbies, which included fishing, and walking on the beach-which had led him to our letter. He asked us to write back. We did, but never got a reply and we’ve often wondered whether our letter ever reached him.

A bottle making its way to Cuba is amazing because it would have had to travel north along the east coast of the United States, around the North Atlantic past England, Europe, and the islands off Africa, then back west, passing below the Sargasso Sea and north of the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola, and missing the southern Bahamas to cross the Windward Passage to Cuba. That’s quite a trip!

I learned much of what I know about the Gulf Stream from the seminal book by William H. MacLeish, titled The Gulf Stream: Encounters with the Blue God. The former editor of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Oceanus magazine, MacLeish explains the physics behind the various currents, or gyres, of the North Atlantic Ocean, weaving together science and historical information, including anecdotes about how the Gulf Stream has affected civilization from the time of explorers like Columbus to modern-day drug dealers.

The North Atlantic contains a number of gyres that are fed by the Gulf Stream. If a bottle rode the Stream past Canada’s Prince Edward Island, for instance, it might get picked up by the North Atlantic Drift, where it could head towards the British Isles or get swept past Iceland towards Norway. But if the bottle ended up slightly to the south, it might be caught in the Azores Anticyclone gyre, and be carried south towards Africa, where it could float in the Canary Current and travel southward along Africa’s west coast. It might also piggyback on the North Equatorial Current, and move to the west, north of the Equator.

That’s probably what happened to the bottle found by Portelles in Cuba, but if you study a chart of the area in question and see how many places a small piece of flotsam like a wine bottle could potentially end up, you begin to understand the awesome randomness of it making its way to the beach near Los Angeles-a small example of marine chaos theory.

We received a number of fascinating returns over the next few years, including a second one from Cuba. We also got a great note from Scott Abernathy of Savannah, Georgia, who spotted one of our bottles while fishing in a billfish tournament 100 miles offshore (in a Bertram no less!). After several unsuccessful attempts at grabbing the bottle in rough seas, Abernathy dove overboard and retrieved it by hand! “We had to have that bottle,” he said.

| | |

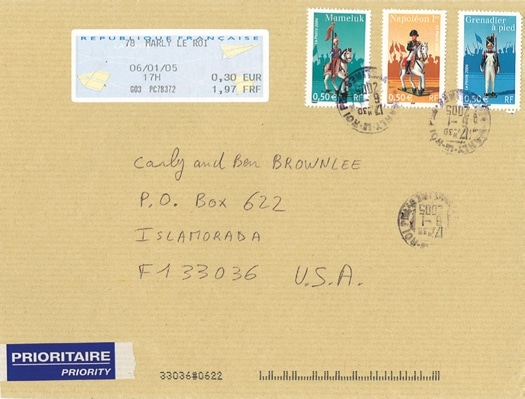

Intrepid beachgoers found our bottles in many different countries, including France, where a French policeman walking with his six-year-old son found a bottle that had been adrift for 5 ½ years. Other returns came from North Wales, the northern coast of Spain, the Bahamian island of Eleuthera, and two from Denmark. Many of these, including the bottles found in France and in the Bahamas, must have traveled all the way around the Atlantic many times before ending up on a beach.

One had been at large a few months shy of eight years. Elsebeth Dalmer of Kolding, Denmark, found one of our original bottles, released in June of 1999, on March 17, 2007. The 47-year-old mother of two made her discovery on the Danish island of Fanoe, and she wrote that she wished a child had found the bottle, but that “I was excited, too, as a child would have been.”

Excitement is a common theme in the message-in-a-bottle business. People are always thrilled to find them, and we’re always thrilled to hear about their discoveries and exchange information about our lives. That’s what makes this minor violation of the MARPOL treaty so much fun.

I’m not exactly sure how many bottles we’ve released over the years because this is a decidedly unscientific venture and we don’t count them, but I would guess it’s close to 100, and 13 have been found so far. That’s an amazing rate of return in my book.

We hope to meet some of these new friends in person someday, and who knows? Maybe when we finally normalize relations with Cuba, I’ll go there and knock on the front door of Juan Arnaldo Rodriguez Portelles in Los Angeles, introduce myself, and ask if he ever got my letter.