Dornier Seaplane

Take the deep-V hull from a high-performance offshore racing powerboat, slap wings on it, and then fill it with the posh interior of a business jet. The result is the Dornier Seastar, which opens vistas never considered, even if you’re already flying by private aircraft. Imagine, if you will, that you want to go bonefishing in the Keys. You’d have to fly or drive down there, rent a boat, and spend a chunk of time getting out to the flats. The Seastar lets you just fly down, land on the water near the flats, and—by the way—the wing makes a terrific casting platform.

Perhaps your boat is at anchor in the Exumas. Getting there is going to be, well, ugly. Airports, connections, and finally a boat ride to your anchorage. The Seastar can land next to your boat and taxi right up to it. Want to make a grand entrance for your getaway weekend at Palm Island or Necker Island? You can’t do better than arriving by Seastar. The thing about the Seastar that works so well with the yachting lifestyle is that it is a true amphibian: It can land and take off with equal grace from land or water.

So, why aren’t there more seaplanes? Up until now, the seaplane has been limited by its basic construction. Face it, riveted aluminum and salt water are just not a happy combination. But the Seastar is built from fiberglass just like a boat, and the one-piece hull won’t corrode or leak.

According to Mac McClellan, editor of our sister publication, Flying, an airplane operated in salt water must undergo a total overhaul with major parts replaced every two or three years. Even with an intensive maintenance schedule and freshwater baths after ocean landings, a metal seaplane is always under attack from corrosion. The high-gloss fiberglass construction of the Seastar reduces the maintenance requirements to a fraction of those for conventional seaplanes.

Dornier is no newcomer to aviation. The Dornier family has built more than 10,000 aircraft over the past century, including more than 1,000 seaplanes. Before World War II, Claude Dornier built a number of seaplanes, including an immense transoceanic flying boat with 10 engines and a wingspan larger than that of a 747. As fiberglass became accepted in aircraft, Dornier began developing the Seastar in the early 1980s and, by 1991, had certification from the FAA, as well as German authorities. Unfortunately, the project was put on hold when the company was sold and it wasn’t until a couple of years ago that Conrado Dornier brought the project back on line.

Since the basic fuselage has been approved for construction in Germany, the company is building the hulls there and finishing the build in the States. But Joe Walker, the CEO of Dornier Seaplane Co. (and former sales head at both Gulfstream and Citation) is setting up production facilities near Montreal to build the entire aircraft. Meanwhile, another Seastar will fly this year, and six more in 2011. The company has deposits for more than 50 Seastars, some of which will go to private owners and some to remote or island resorts that want guests to arrive in style.

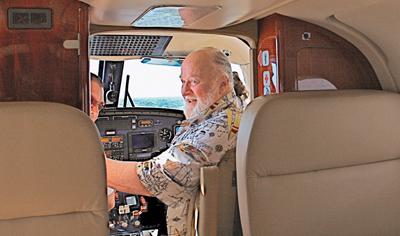

The Seastar passenger cabin is 18 feet long, or more than five feet longer than a Cessna Caravan. The cabin, at five feet, seven inches, is also wider than the King Air by more than a foot. And the headroom of four feet, six inches is more than that of the Caravan. The aircraft that McClellan and I flew is number two, and it was fitted with the standard nine-passenger interior, equipped with supremely comfortable UltraSuede seats, highgloss burled-wood bulkheads, and carpets befitting a Rolls-Royce. Dornier also offers a luxury six-passenger interior, which ups the amenities with an enclosed head, or another configuration, a high-density interior for up to a dozen passengers plus their luggage. Our preflight walk-around revealed some fascinating details. Seastar has a parasol wing, which stands on struts, giving the propellers clearance above the cabin. The twin-turboprop engines are in a push-pull arrangement in line with each other. The engines rotate in the same direction but, because one is reversed, the propellers are contra-rotating for better efficiency. By keeping the engines centered over the hull, the rolling moment is reduced, enhancing stability on the water, and the height keeps the engines and propellers far away from salt water.

Complex may be the best one-word description of the hull. The deeply veed main part of the hull morphs into a pair of wide sponsons on each side. The inner section of each sponson has flattish chines, and the outer section is softer in shape. At rest in the water, the inner section is fully submerged, and the outer acts like the amas of a trimaran, so the Seastar doesn’t require floats at the wing tips for stability. The sponsons also hold all the fuel, which keeps the center of gravity very low.

As soon as the Seastar starts to move, the inner sections of the sponsons generate tremendous lift to pop the aircraft onto a plane for fast and short takeoffs. Landing is just the opposite: The deep-V kisses the water first and the sponsons continue to soften the process as the aircraft drops into displacement mode.

Getting aboard from the wide, non-slip surface of the sponson is equally well planned, with a large gullwing door for the pilot and a wide hatch into the cabin from the port side. Skippers will be amused by several surprises. First is the mooring cleat next to the pilot’s door. A boarding ladder is hidden under a locker on the sponson and, while it is primarily for dry land, it doubles for swimming, although I’d like a rinse-off shower nearby.

Settled in the cockpit, there are more surprises in store. First, the power controls are mounted on a pedestal between the pilots, unlike most seaplanes, which have the throttles hanging from the overhead at eye level.

Second, there were an unusual number of warning lights for the landing gear, which makes sense because landing on the water with your wheels down is the one Bozo No-No of seaplanes. This particular plane had a classic aircraft avionics panel with round gauges, but future Seastars will have a full glass cockpit with interfaced monitors.

Power for the Seastar comes from a pair of inline Pratt & Whitney PT6A turboprops. These Dash 135A versions put out about 650-shaft horsepower and are the same as those used in the Beechcraft King Air 90. Taking off from the Punta Gorda, Florida, airport where Dornier is based was effortless, and I was impressed with the low noise level. Even at full takeoff power, the cabin was far quieter than I would have expected with two big turboprops howling away just overhead. McClellan was up in the right seat, and his first-time landing on Charlotte Harbor was soft and impressive, although his many years as a racing sailor give him a good eye for wind and sea. The Seastar takes off from water in less than 2,500 feet and, even with one engine out, still climbs at almost 500 feet per minute.

The Gulf of Mexico glittered in the sun beyond Captiva and Sanibel Islands and, with a lazy “Why not?” we headed out to sea. It was a calm day and so—get this— we landed so far out that Florida was just a haze on the horizon. We touched down, killed the two engines and were enveloped in silence. Aside from the faint tink-tink of cooling engines, the only sound was the slap of water on the hull. Joe Walker popped open the rear hatch and handed out icy soft drinks from the fridge. We all stepped out onto the sponson, which was our private porch in the shade of the wing, somewhere in the middle of the ocean.

The Seastar has a high-speed cruise of 180 knots and, with a fuel capacity of 458 gallons, a range of 700 miles is reasonable, depending on the load.

Driving home, I couldn’t stop thinking about the possibilities. Land somewhere in the Bahamas and put the nose on a deserted beach for a picnic and a swim before flying home. Drop a Royal Coachman fly in front of a rainbow trout on an isolated mountain lake, explore the Sea of Cortez in grand style, or catch up with your yacht wherever it happens to be.

Dornier Seaplane Company, (800) 590-9667; www.dornierseaplane.com