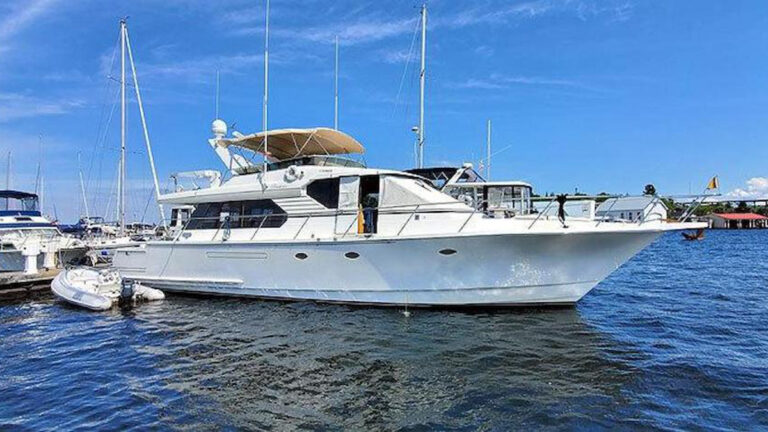

A sales pal of mine called the other day in a huff. He’d just listed a lightly used, factory-fresh, 50-foot yacht. It’s a high-tech, high-performance media darling that’s in such demand there have been lines of fans around the block waiting to experience its performance. Unfortunately, one of its engines had lost its voice.

“Can you believe it, Coyle?” he said. “It’s got the latest smart-outboard technology screwed to its transom, and I can’t get them to agree to take a customer on a sea trial.”

My pal explained that the four motors were not playing well together. “One of the motors refuses to talk and is butting heads with its siblings.” Hmm, got a couch?

I spent my formative years as a skipper aboard a 13-foot Boston Whaler dealing with an 18 hp two-stroke that was as dumb as a rock and willfully stubborn. After endless sessions of pull-starting and manipulating the choke, it was clear that one of us was going to need therapy. I then got wise to what was going on under the hood, learned the basics of carburetion and spark ignition, and invested in a bag of tools. Oars and oar locks were fitted, just in case.

Outboards had come of age when I graduated to a 20-foot SeaCraft in 1970. Its 115 hp two-stroke was fairly well behaved. I still carried a bag of tools and had a 4 hp kicker screwed to the transom, just in case.

There were tools aboard my 1980 25-foot Mako, and two 150 hp two-strokes, just in case.

The 150 hp two-stroke that joined my fleet in 1996 was well behaved in my care and is still running today. The 150 hp four-stroke that followed in 2010 was a game-changer—at last, an accomplished solo performer. A gasoline motor doing a handstand inches above the transom wash was arguably as reliable as an inboard diesel.

Read More from Jay Coyle: Tell Tales

So what happened? Since the days when a branch was whittled into a paddle, designers have been driven by more-is-better thinking: If one is good, two is better, and if that’s not enough, add even more. If Charles Lindbergh’s motor had crapped out over the Atlantic, he’d have had a long swim. His odds of staying dry would have increased with two engines, right?

It depends. Amelia Earhart’s second engine was apparently no help; in fact, it’s possible that she ran out of gas feeding it. Given the tragedy, did designers pause and reflect on the cost of added appendage drag, increased fuel consumption, weight and complication? Of course not. It took them just 20 years after Lindbergh’s landing in Le Bourget to noodle the eight-engine Spruce Goose, which seemed too much of everything.

Water or air, the ultimate goal is to transmit horsepower into the vehicle with the fewest moving parts. Weighted for redundancy, two motors seem to be the gold standard. As designers have yet to create a 1,200 hp outboard that can turn a 40-inch wheel, “more” will simply have to be better—behaved.

Got a couch? I still carry a bag of tools. You know, just in case.