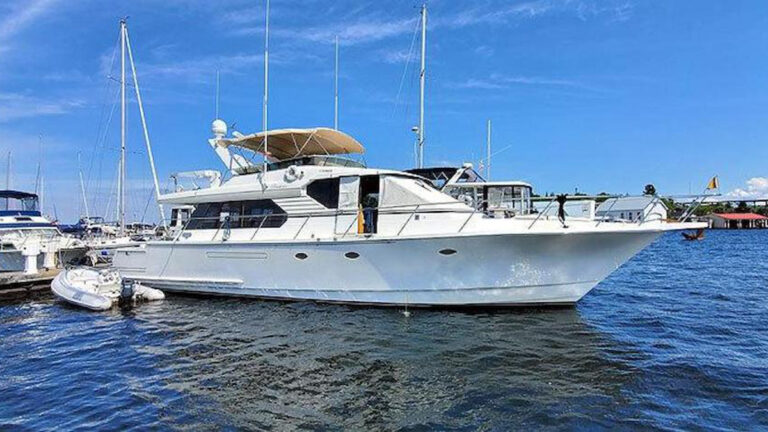

Recently, a boatbuilder pal shared a rendering of a “breakthrough” in yacht design that’s been making the rounds in the media. I was confused.

“What’s that thing sticking up in the bow?” I asked. “That is the bow?”

“Its head,” my pal explained. “Don’t you see? It’s a bird. It goes up and down.”

A 400-foot decoy for a half-billion dollars. Good God! I suggested that driving the bird with the head up in a sea would be like clinging to the masthead of a square rigger rounding the horn.

“Coyle, you’re thinking too much,” my pal said. “Use your imagination. This is the future.”

The late designer Francis S. Kinney came to mind.

My career would not have been possible without Kinney’s updating of Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design, which was first published in 1904. While Archimedes had figured out why stuff floats more than 2,000 years earlier, Norman L. Skene, an MIT-trained naval architect, explained how to shape stuff into a proper yacht. Kinney earned an architecture degree from Princeton University in 1938 and adopted the cause, serving more than 30 years at the iconic yacht-design firm Sparkman & Stephens.

As was the case with most of my peers, I had studied Kinney’s last update, circa 1973. It provided a road map for design students of my generation so that we might avoid disaster by design. The math, science and art of yacht design was offered with real-world examples that had actually worked.

It had been years since I cracked the cover, so I dusted off my worn edition in search of wisdom. In the first few pages, a hand-drawn illustration of a launching gone south titled “Naval Architect’s Nightmare” spelled out the risks of calling yourself a designer. Kinney described seeing news images from 1952 of waving flags and spectators as the Italian tanker Piero Riego Gambini slid into the water, briefly considered its new home and keeled over. Kinney’s message to aspiring designers was simple: Do the math or find a new line of work.

In addition to promoting the benefits of carefully noodling numbers, Kinney urged designers to use common sense. Humans have to move comfortably and safely aboard boats, as well as have proper access for maintenance and repair. He provided the minimum interior dimensions required for these tasks and noted that the cursing and swearing of engine mechanics on repair jobs is not without good reason. The takeaway: An owner who bangs his head reaching for his wallet to pay a boatyard to dismantle his boat to change a fuse will soon find a new designer.

Then, I found it, the words of advice I’d heeded 40 years ago: “Since the caveman’s log canoe, good design makes use of that which has gone before. … There is a happy medium between extreme originality and novelty.”

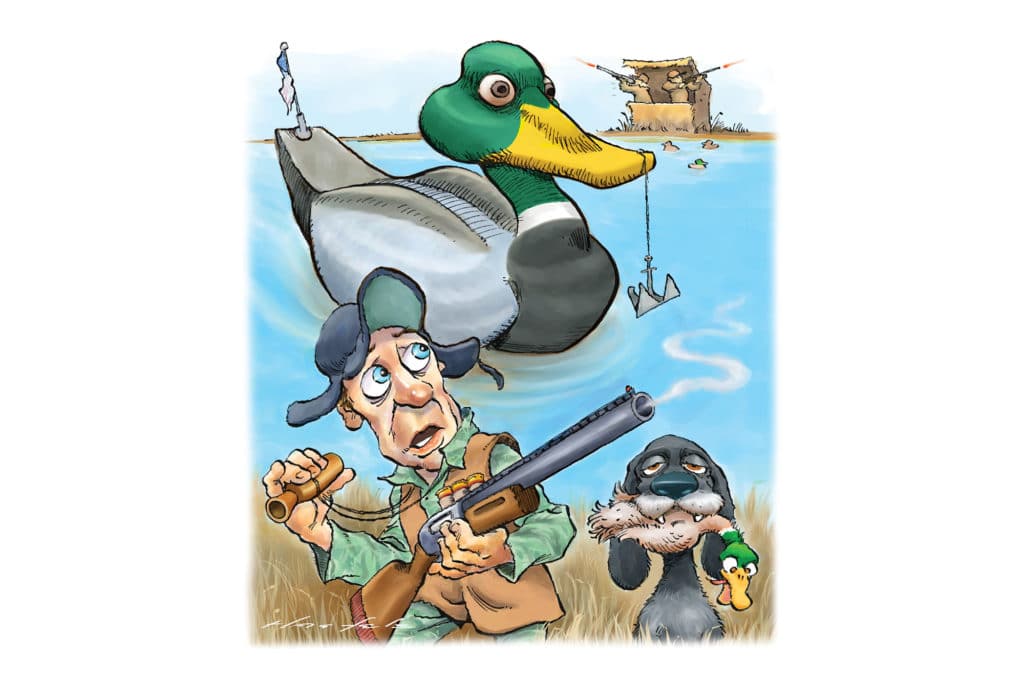

“This decoy is a novelty,” I said to my pal.

“Coyle, this is a new age,” he groaned. “If ya wanna attract today’s boat buyer, simply write down what you know is impractical and ridiculous, tell engineering to make it work, and start construction before another ‘breakthrough’ comes along.”