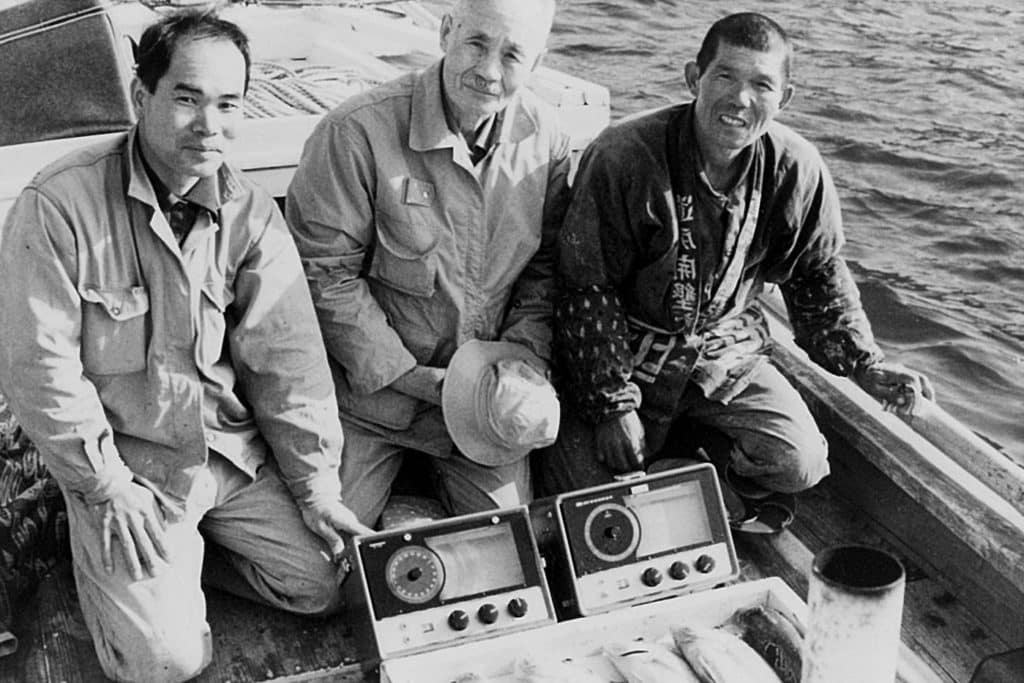

The Furuno Brothers

Transforming the fishing experience

Could one argue that the invention of the modern fish finder was anything less than revolutionary in the recreational-boating world? Certainly not. And while many people believe the fish finder to be an American invention—U.S. companies certainly made them widely available to recreational anglers—the invention of the first fish finder can be traced to a pair of brothers in Nagasaki, Japan, shortly after World War II.

As early as 1942, Kiyotaka Furuno knew fishermen in Kuchinotsu Harbor looked for bubbles on the water’s surface to locate fish. In fact, anglers claimed they could estimate the size of the catch by the volume of bubbles. Kiyotaka and his brother, Kiyokata Furuno, thought of building a machine that would find fish by first locating those air bubbles and then by reflecting sound waves against the bubbles. Little did they know, the fish themselves made excellent reflectors for bouncing sonar waves, and their ideas would change the way anglers hunt for fish.

Rudimentary sonar was developed during World War II to detect submarines. In 1945, Kiyotaka Furuno began piecing the first fish finder together with scrap parts available after the war. While working at their electrical company—where they repaired radios—the brothers began experimenting on the water, fine-tuning the first fish-finding sonar units. There were numerous failures, and most people thought finding fish with sonar was impossible. But a breakthrough occurred when the Furuno brothers installed a transceiver through a hole in the bottom of a boat: the first through-hull transducer.

“Their persistence paid off when, in 1948, the brothers demonstrated that they could successfully identify shoals of fish far beneath the water’s surface,” says Jeff Kauzlaric, Furuno’s advertising and communications manager. “Their first catch? Sardines. They formed Furuno Electric Industries on December 3, 1948. By the end of 1949, the entire fishing fleet of Iwaseura, Japan, had Furuno fish finders aboard.”

The first commercial unit Furuno produced was a paper graph recorder. The mass market would abandon this technology in favor of “flasher” units that displayed blinking lights on a scale, and it would be decades before paper graph recorders came back into style. Today, of course, fish are displayed on LCD screens in shocking detail; they can be detected to the sides of a boat and in front of it, as well as below. Modern fish finders trace their roots to these brothers, searching for bubbles. And Furuno’s mantra is based on the principle Kiyotaka Furuno coined: “Furuno doesn’t sell a box of equipment to our customers,” he said. “We sell them results.” —Lenny Rudow

Seven Marine

Supersizing outboard engines

Less than a decade ago, a handful of outboard-powered boats stretched into the 40-foot range. Today, there are hundreds of these boats, the largest of which is 65 feet in length, with 50-footers becoming commonplace. And in no small part, credit for that upsizing goes to the Davis dream team.

Seven Marine—led by father and co-founder Rick Davis and vice presidents Eric and Brian Davis—made bigger outboard boats possible when it shattered the 500 horsepower barrier in 2011 with the Seven Marine 557. Less than five years later, the company set another benchmark with the 627, which remains the most powerful outboard today.

Rick Davis’ place in marine history already seemed cemented after more than 40 years in the industry, including serving as vice president of engine development and advanced engineering for Mercury Marine. But after retirement from Mercury, he simply wasn’t finished. He founded Davis Engineering in 1998 with sons Eric and Brian, both of whom had engineering minds and hearts made for boating.

“Brian and I grew up together as best friends, racing competitively against each other,” Eric Davis says. “We quickly learned we each had unique attributes that, when combined, made us hard to beat. Applying that learning to business kept the brotherly arguments to a minimum and progress to a maximum.”

Rick Davis also credits racing as a family as an important learning component.

“We learned that preparation and organized thought is key,” he says. “We each try our best no matter the outcome, but if we aren’t winning, we ask what we’re missing and how do we get that right.”

Developing the world’s largest outboards would require every bit of the Davises’ collective knowledge. Brian and Eric say they had to challenge nearly every aspect of conventional wisdom about how an outboard is constructed, while respecting its function. Fortunately, they had Rick’s seasoned outboard design philosophy to temper their out-of-the-box thinking. Meanwhile, Eric thought to create a horizontal business model—like a sterndrive—where components such as engines and transmissions could be leveraged from other companies. Weight, cost, package size, psychographics, demographic data specific to outboards, and market trends were all considered.

It worked.

Even with Volvo Penta’s recent acquisition of Seven Marine—where the Davises all still work—the innovation is expected to continue. “This marks the next logical step in our ongoing technology journey at Volvo Penta to explore new designs, technologies and architectures that will transform the global marine industry,” says Ron Huibers, president and CEO of Volvo Penta of the Americas and chairman of Seven Marine. “Our goal moving forward is to broaden our technology platforms and offer cutting-edge solutions, regardless of the energy source, to deliver the desired power on the water.”

There’s one other critical component to Seven Marine’s success: “We are always on,” Eric Davis says. “Our wives and children wonder if we ever think of anything other than huge outboard motors.” —Lenny Rudow

48 cruiser

Wisconsin-based Burger Boat Company has been combining new technology into a surprisingly small package. In late 2017, the builder announced plans to build a 48 Cruiser—a far smaller boat than what the world had come to expect from Burger, but one that brought innovation through the use of Vripack’s Slide Hull, Volvo Penta’s IPS propulsion and Luiz De Basto’s interior design. Vripack and De Basto are more regularly associated with far larger yachts, which is why the Burger 48 Cruiser has such an upscale look and feel. Modern technology included Volvo Penta’s Clear Wake System, which directs exhaust above water at anchor to prevent “gurgling”; a Seakeeper 6 gyrostabilizer to reduce roll by as much as 95 percent; and Volvo Penta’s Interceptor system that provides autotrim. Burger also built the boat out of Alustar aluminum, allowing for a lifetime warranty on the hull structure and a five-year warranty against blistering. —Kim Kavin

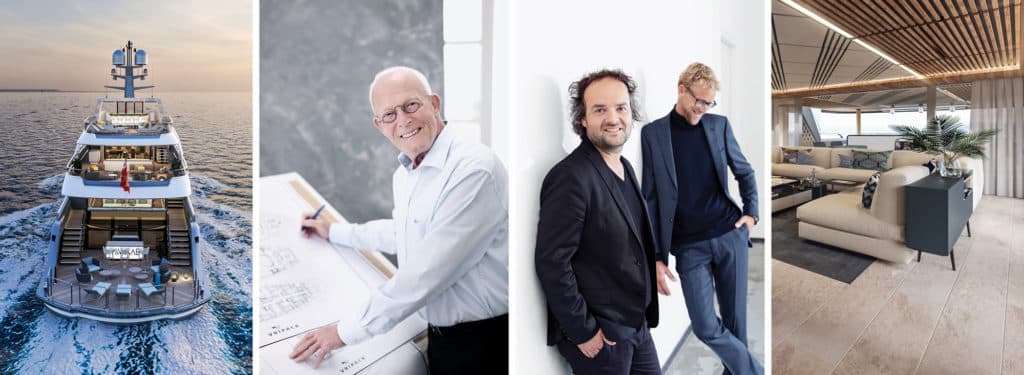

Vripack

Designing yachts that span style and size

Vripack, in the Netherlands, has been seen as an innovative design firm almost since 1961, which was the year Dick Boon sat at his drafting table to create Hull No. 1: a lovely, if unassuming, 21-foot wooden sailboat.

It took another seven years for the first Doggersbank to emerge from his mind as a steel-hull, go-anywhere vessel—and to win the hearts of bluewater cruisers the world over. Doggersbanks were later built in other materials and evolved into an entire Doggersbank Offshore line starting in 1985. The first Doggersbank Explorer launched in 2000, at a time when yachts were growing exponentially in size; it was a scaled-down version of a 280-foot concept yacht. With today’s trendsetting yachtsmen looking for expedition styling and go-anywhere capabilities in increasing sizes, the original Doggersbank is now considered a springboard design decades ahead of its time.

And Vripack has continued to expand far beyond the Doggersbank concept. Now under the creative direction of Marnix Hoekstra and Bart Bouwhuis, the firm has used everything from computer-assisted design software to virtual reality technology when working to innovate its drawings for vessels in all size ranges.

Just a handful of Vripack’s recent projects show the breadth of the firm’s capabilities. For starters, in summer 2018, Vripack and Wisconsin-based Burger Boat Company unveiled Hull No. 1 of the Burger 48 Cruiser, with Volvo Penta IPS engines and Vripack’s Slide Hull, which is promoted as reducing pounding and eliminating bow rise as the boat gets up on plane.

“They presented it, and we said, ‘OK, prove it,’ and we tank-tested the boat, and the test showed exactly what they said,” says Ron Cleveringa, Burger’s vice president of sales and marketing. “We built the boat, and it performed how they said it would.”

Cleveringa says he was completely sold on Vripack’s Slide Hull concept after being out on the Burger 48 in nasty Lake Michigan waters.

“I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t a bang or two,” he says, “but if you’re in 7- to 10-foot seas and you get a bang or two in six or seven hours, that’s pretty impressive.”

Vripack is also working on yachts of various sizes with California-based Nordhavn, which has long been known for its go-anywhere bluewater cruisers. Jim Leishman, Nordhavn’s vice president, says he was impressed with the analysis Vripack did using computational fluid dynamics on the Nordhavn 41.

“They took the hull lines and ran it through this sophisticated process and came up with suggestions for how we could improve efficiency,” Leishman says. “It was pretty revolutionary compared to the tank testing we’ve experienced in the past. With tank testing, you build a model, and the testing confirms or disconfirms the boat; with computational fluid dynamics, it shows you exactly where the pressure points are that are creating resistance. It helps you to refine the hull, and then you run it through the testing again and see the results. It’s like being able to build 50 different models to find the one that will perform the best.”

The experience was so noteworthy, the two companies decided to collaborate on larger projects. In late 2018, Vripack again teamed up with Nordhavn to announce the Nordhavn N80; Vripack is currently developing the interior for the newest N80 hull in production. And going forward, the two companies are working together on a Nordhavn 135 that was announced at the Fort Lauderdale International Boat Show in November.

“With Vripack’s world-renowned expertise and help,” Leishman says, “Nordhavn is expanding more into the European and international marketplace with new and exciting designs.”

Also in the superyacht range, just a half-year after announcing the Nordhavn N80 model, Vripack announced it had been working with German yachtbuilder Nobiskrug on a 183-foot asymmetrical concept yacht with hybrid propulsion and a wide-ranging use of structural glass for the exterior design. To allow room for all the unusual interior features—such as hallways that change width as you move through them—Vripack specified “pancake-style” engines that are flatter instead of tall, to keep the engine-room space minimal.

That yacht is intended to create an entirely new segment of business for Nobiskrug, according to Fadi Pataq, the yard’s creative director. The builder believes it will appeal to “entry-level” clients who aren’t quite ready for the more than 300-foot-long yachts for which Nobiskrug is known.

Being able to think simultaneously on so many different levels—about so many different yacht sizes and styles, construction materials and features, and technological advancements—is what sets Vripack apart as a design firm in some of the world’s most renowned shipyards, according to Cleveringa.

“They’re very similar to other companies in terms of professionalism, but they do tend to push the envelope of innovation and the way they do things,” he says. “They’ve come up with some different ideas on construction practices. They’re constantly willing to learn.” —Kim Kavin