A few years back, I had the chance to photograph Land Rover’s off-road driving course called the Land Rover Experience in Quebec, Canada. While snapping images and swatting black flies, I had an epiphany. Forget the damn tail fins; this is something the marine industry could borrow that would benefit boaters, even old hands.

During my earlier years in boating, I went through a handful of lesser boats before graduating to a 37-foot Bertram convertible. As a yacht designer and licensed captain, I assumed I knew it all. But I didn’t. It took me 22 years to learn her ways, and the truth is that after 57 years on the water, I’m still learning from my mistakes.

Like most boaters of my vintage, I started out small. After graduating from plastic speedboats in a wading pool, I earned the helm of a newfangled “plastic” tender, a 13-foot Boston Whaler. For a 10-year-old, sheltered inshore waters were like an ocean. And those waters were a safe bet, with far fewer boats and boaters, and just 18 hp on my transom.

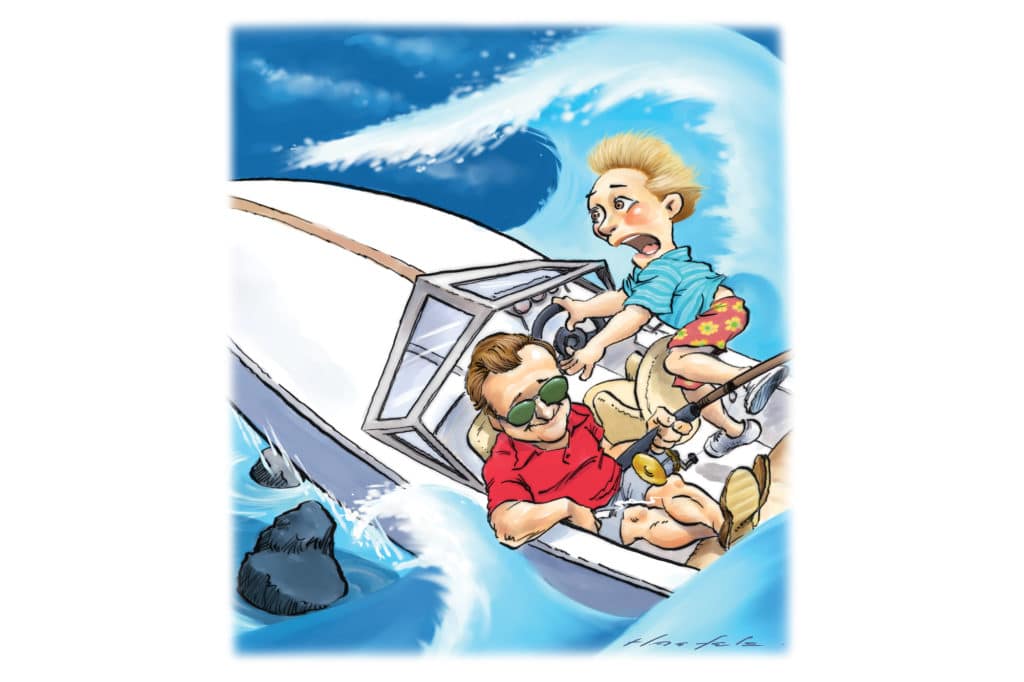

Pop was nearsighted when it came to boat handling, and I learned a lot from his mistakes. When Pop invested in a new 233 Formula, I was all in. The 23-footer was a product of Don Aronow’s passion for racing and of racers Jim Wynne’s and Walt Walters’ passion for design. Pop was passionate about chasing sailfish, and challenging inlets rarely tempered his enthusiasm. I often took the helm as a matter of self-preservation. The Formula saved us from ourselves and inspired my career in yacht design.

The pace was a lot slower back then, and for Pop and me, it was a luxury to learn from our mistakes. There were no thrill-seeking PWC enthusiasts or windsurfers flying about. Inlets—and the ocean beyond—were treated with greater respect. Kids today are likely to start out at the helm of a 50-knot center-console, and my fellow fogies need only a checkbook to qualify.

Read More from Jay Coyle: Tell Tales

A license and a checkbook are required to own a Land Rover, but to really drive one, you also need experience. Land Rover offers that experience at three schools in the United States and one in Quebec, where I found myself clicking pictures of a group of corporate types engaging in some team building. Learning to play well with others is a popular group activity for white-collar sorts; teamwork is an asset common among the best yacht crews.

The exercises involved skippering Land Rovers through a course designed to push drivers and vehicles safely to their limits. For many, it was their first time off the pavement. I’ve been an off-road enthusiast since 1975, and the experience still benefited me. The lessons focused on calculating an appropriate use of power and anticipating the vehicle’s response to the environment. These are the same skills a skipper depends on in nasty seas or rough inlets.

There are options for hands-on training in boat handling and seamanship, but they arre limited. It would be great if more manufacturers embraced the idea. Or, perhaps, if Land Rover built a boat. Just, please, no tail fins.