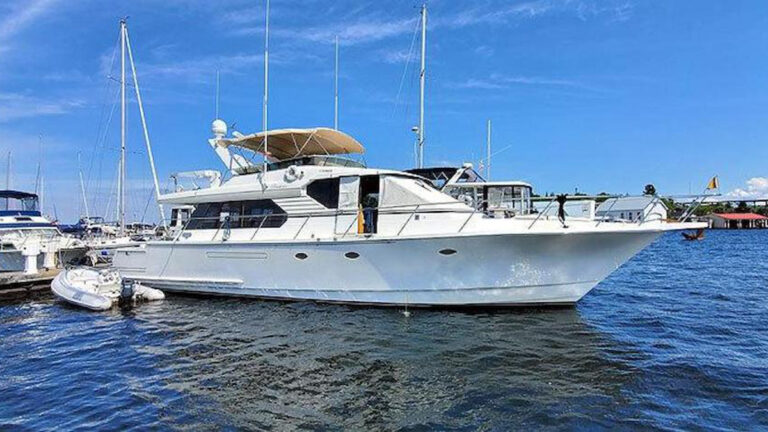

Wombat

The sun rises early along the mid-coast of Maine, and in November it can be as brilliant as an arc lamp, unkindly revealing imperfections and the wrinkles of age. But Wombat, the star of today’s show, seems unconcerned about her close-up. As an aurora borealis of sunlight dances on the coffered overhead of her bridge-deck saloon, set in motion by cat’s paws on the surface of the water and reflected through chinks in the mini-blinds, no flaws come to light.

While I sit at the dinette beside a member of the delivery crew who’s checking off supplies for the trip south, my imagination momentarily drags anchor. Here I am, sipping espresso and reading The Economist, deciding which company to buy today. Such are the fantasies enabled by Ward Setzer’s design and Lyman-Morse Boatbuilding’s execution.

But the quality here is no fantasy. When I see the inlay that circumnavigates the table a hand span from the edge, I am moved to wonder out loud: “How are humans able to do such delicate work without apparent flaws?”

J. B. Turner, the gracious managing partner at Lyman-Morse, chuckles in response, then admits that he, too, is awed by the skill and patience of the company’s woodworkers. I step behind the custom teak wheel, made all the more imperial by inlays of wenge. This tropical hardwood grows in West Africa, Zaire, Cameroon and Tanzania; these particular inlays come from trees 60 to 90 feet tall, and their color ranges from dark brown to black while fine black veins highlight the straight grain. Wenge has a coarse texture and is hard enough to quickly dull the cutting edge of machine tools. The presence of so many wenge accents in the joinery and cabin soles adds to the yacht’s luster.

Located on the centerline, the helm presents all of the important instruments and screens within my sightlines. Pulling out the footrest, which slots into the cabinetry below the seat, I park myself as though I were a regent. From this perch, I easily see the bow and the caprail on the transom (plus my surroundings on each side). The corners of the transom are not visible, however; when the helmsman has to back into a tight spot, he’ll do so from the control station in the cockpit.

The Setzer Design Group also arranged all of the controls to be within easy and intuitive reach from the wheel. Although the autopilot will steer Wombat on long passages, its ergonomically designed helm console should inspire the driver and help relieve the stress of maneuvering in close quarters when the wind and current fight every move.

Stepping away from the helm, I slowly sort through all the visual stimuli. So much varnished wood is lovely and traditional; it warms up an otherwise austere ambience. In some yachts I’ve seen this much wood create a sepulchral mood, particularly if the owner has selected an overly dark stain or requested overbearingly large motifs, but though Wombat‘s interior flirts with the dark side, it doesn’t go over the edge. It helps that the coffered overheads throughout the yacht are paneled in white; I would even lay in more white, were she mine. As a measure of her proportionality, masterfully turned and delicate balustrades on the staircases, and on some of the fiddles throughout, significantly reduce the sense of mass.

Woodworkers at the premier American builders rival those of the famous European yards, as careful examination of Wombat‘s interior proves. Simply looking at her joinerwork doesn’t satisfy; you have to run your fingers over the barely visible joints, caress the many carvings. Ornamental valences hide the HVAC outlets around the perimeter of the cabins; LED lighting, also behind the valences, sets the mood to romantic.

Down a few steps and forward in the galley, counters of solid granite add to the yacht’s feel of strength, durability and place within the natural world. Natural light cascades from the windows of the pilothouse, and will sauce the chef in its buttery glow. The plan spares the occupants of the bridge-deck saloon the sight of the galley’s machinations, but lets everyone on the two decks savor the fragrances.

Similar imaginative touches distinguish Wombat‘s galley. Stowage cubbies, let into the structural base of the settee on the bridge deck, are particularly clever in their use of space-and their contents are closed off from view by roll-top doors. One of these cubbies houses the microwave oven, the other, anything the chef desires. A slot next to the trash compactor stows large serving trays or sheets. Cabinets above the counter secure the dinnerware. Every component of the galley works in harmony, and every tool-large or small-has its place (out of sight). A hatch directly over the cook top will let the heat of cooking escape the galley when the yacht anchors in areas of temperate climate. Cool fresh air entering via the galley’s porthole will accelerate the flow.

The guest stateroom in the forward section of the yacht has a pair of single berths set apart by a comfortably wide passageway and nightstand. Skipper and crew share a large stateroom forward of the galley, with a queen-size athwartships berth, spacious head and enough stowage (two hanging lockers, nine drawers and bins under the electrically lifted berth) to satisfy even Imelda Marcos. This cabin would be an ideal VIP suite if the owner decided to run the boat without his skipper; as it stands, Wombat‘s skipper and his wife-mate-chef may count themselves among the most fortunate professionals in the business.

A foyer, paved in teak and holly, welcomes me to the master stateroom. If the state of Maine had a king, he would live in palatial surroundings similar to these. The stateroom occupies a substantial number of square feet between the machinery space and the engineroom. This location offers the best ride when at sea, the faint bass hum of the C18 Caterpillars supplying exactly the right amount of white noise to assure a sound sleep. Although the location-under the bridge-deck saloon and cockpit-eliminates the overhead hatches that I prefer, portholes provide a respectable amount of natural light. Excellent electric lighting more than compensates for any deficiency.

Crowned by a mahogany headboard, a king-size berth on the centerline dominates the space. A pair of doors, flanked by ornate columns and opposite the foot of the berth, open onto tall and deep-hanging lockers. The master head has two sinks separated by a counter, eight drawers under, a porthole, a luxuriously large shower, and a separate room for the toilet.

By the time we were ready to depart for a sea trial on the St. George River, Turner had returned, attended by Cabot Lyman, multihull designer Nigel Irens, a client of Irens’ looking for a builder, and the client’s project manager. We totaled 10, maybe 12, but when the skipper had fired up the big Cats to let them warm, everyone could be heard; only a slight vibration through the soles of my feet told me the engines were running.

The way Cabot Lyman tells it, Wombat is a larger version of Magpie above the waterline and a shorter version of Acadia below. She’s 6.5 feet longer and 1.5 feet wider than Magpie. The extra length allowed Setzer to draw a longer bridge-deck saloon/pilothouse and provide a patio-like cockpit at the same level. Back there, I found a grill, sink and cooler-all of which will serve the owners during casual entertaining. Extending the pilothouse/saloon also permits stowing the dinghy on the roof.

Lyman-Morse commissioned Janicki Industries in Washington State to cut a new stern section for Acadia’s mold. This shortened the overall length and added tumblehome to reduce the yacht’s visual bulk back aft. Below the waterline, Setzer drew shallow tunnels for the propellers. Unlike some tunnels I’ve seen, Setzer’s tunnels merge with the run so subtly that they defy detection. As a result, solid water flows smoothly to each prop.

How Setzer makes an 80-foot yacht handle like a runabout is a mystery to me. Yes, I’m exaggerating to make a point, but the fact remains-Wombat is exceptionally responsive for a yacht her size. Seakindly, too, though we had only our own wake upon which to base that conclusion. Reports from the skippers of Setzer’s other classic designs, however, reinforce my statement. Digital stabilizers damp roll and let her corner without leaning.

A yacht of this caliber transcends the quest for speed. She’ll cruise for days at 1800-1900 rpm, making from 14 to 16 knots depending on the state of the sea, and burning about 30 gallons of fuel per engine every hour. She’s as comfortable as any reasonable human could want, and quieter than normal conversation. If that’s not enough, she can provide hours of quiet contemplation-all the owners have to do is dinghy away from her at the mooring and feast their eyes. n

Contact: Lyman-Morse Boatbuilding, (207) 354-6904; www.lymanmorse.com.