Transatlantic Sailing

For blog entries from this amazing journey click here.

The wind howled out of the pitch-black night as I watched the anemometer climb to nearly 30 knots. The sea was running 8 to 12 feet, slapping against our starboard quarter and making for an uncomfortable ride. I clung to the wheel before me as we pounded through the waves. It was 0100, November 23, and the previous morning I had set sail from Las Palmas, on the island of Gran Canaria. I was on a Hanse 461 with two Brits I’d met a few days before, and the next time I would set foot on land would be in St. Lucia, more than 2,700 nautical miles away.

It’s All About the Prep

Five days earlier I was standing on the balcony of my hotel room, looking out over Puerto de la Luz and thinking, “Am I really sailing home?” Ever since I was a kid aboard my uncle’s Beetle Cat, I’ve been obsessed with sailing, and after my first offshore sail, a transatlantic crossing beckoned. But the idea of sailing across the Atlantic, or any ocean, was something that always seemed too big to happen, too much of a dream to become a reality. In the weeks leading up to my departure, with all the preparation that had to be done before boarding my flight, I had pushed the fact that I was finally about to sail across the Atlantic Ocean to the back of my mind. I was embarking on an adventure that I’d never forget (and I had no idea what a great icebreaker—”Oh, the tan? I just finished sailing transatlantic,” would be when I returned to New York).

Las Palmas is an ideal location for a transatlantic sendoff. A city that once called Christopher Columbus its mayor, Las Palmas sits on the northeastern shore of Gran Canaria, about 250 nautical miles west of the Sahara. I was taking part in the World Cruising Club’s Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC). With help from my YACHTING colleagues and World Cruising Club organizers Jeremy Wyatt and Andrew Bishop, I had found a berth aboard Snark with her crew, Ben Little, the owner and skipper, and his friend Dugald Moore.

At the Muelle Deportivo marina, the masts of the fleet stretched above the piers like the top of a forest. The types of boats participating in the ARC, and the nationalities signaled by their flags, seemed to run the gamut: From Zahara, a Sadler 29 hailing from Great Britain, the smallest entry, to the Swan 112 Highland Breeze, one of the seven vessels flying the U.S. flag and the largest in the fleet, to the sleek Wally 80 Bagheera, the lone Turkish entry. There were vessels hailing from Malaysia, Slovenia, Croatia, Israel— in all 31 nations were represented in the fleet, sailing on an array of yachts, from production boats like Jeanneau, Oyster, and Beneteau, to one-off and custom designs, and high-performance racers.

I found Snark and rapped on the hull. A man with a dishtowel wrapped around his head and a patch on one eye popped up from below. Okay, I thought, second-guessing my choice of vessel, they’re pirates. I’ve signed on to sail across the ocean with two men who think they’re pirates. Great. Ben and Dugald, both 40 and longtime friends from England, welcomed me aboard and handed me an eye patch and dishtowel of my own. Once I learned the inspiration for their attire (the off-color British cartoon The Adventures of Captain Pugwash), I knew we’d probably get along just fine.

After a night of carousing, we set about getting the boat ready for the crossing. We needed to make sure everything was working properly: So we checked the lifelines, the EPIRB, the life jackets and harnesses, the liferaft, the fire extinguishers, the engine, the generator, the watermaker, all of the electronics, the rig, sails, and lines—everything from the keel to the top of the mast. Thanks to Snark’s sound condition and with the help of “Jerry the Rigger,” we were ready to go after a few minor tweaks.

We’re Off!

Sunday morning arrived and I felt as though I were standing on the edge of a cliff before leaping into the water below. Down at the marina, even at 0700, the docks buzzed with activity and some sailors looked as though they’d been working through the night to prepare for the 1100 departure.

With Ben at the helm, Snark slipped into the harbor, which was chock-a-block with boats—ARC boats, spectator boats, committee boats, RIBs shooting this way and that. We killed the engine, raised the sails, and positioned ourselves for the start. As the sound of the firing gun cracked the air, we set our sails, hoisted our spinnaker, and, as Ben said, “Sliced through the fleet like butter.” I looked off the stern as the buildings of Las Palmas blended into the hills, Gran Canaria melted into the sky, and it all disappeared over the horizon. “Well, now there’s no turning back,” I thought. We had an excellent start, and by the time the sun was setting, we’d left most of the other boats in our wake.

Ocean, Ocean, Everywhere

After a night of rough waves and sporadic sleep, I came topside to behold a sight I’d never seen before—ocean, and only ocean, as far as I could see—just the dark blue of the Atlantic. We set our course for St. Lucia, trying to stay west/southwest, sticking as close to the rhumb line as possible. The seas hadn’t subsided, but thankfully they were astern, making for a much more comfortable ride, and the wind was still a steady 20 to 25 knots. Under a double-reefed main, with our genoa flying, we made 8 to 8 ½ knots. Before we’d left, we worked out our schedule for night watches—we would each take one four-hour block starting at 2000 and ending at 0800. The first night Ben had taken us through into the morning. Now, he was exhausted, and slept below while Dugald lay in the cockpit and I manned the helm. Standing behind the wheel with the sun on my face and the wind in my hair and nothing around me except the blue expanse of the Atlantic, I felt alive, and freer than I can describe. This was living.

The departure from the daily grind was something that we all enjoyed. “I’ve worked hard for 18 years [as an IT management consultant],” Ben told me one day. “I’d often thought of taking a sabbatical to go and do some sailing, and the opportunity presented itself, so I was keen to do it.” The timing was right, and the World Cruising Club’s resources and professionalism made him choose the ARC. “I was a little bit nervous about sailing transatlantic because it was a much bigger voyage than I had ever done before,” Ben said, “But I was comforted by the organization of the ARC and the fact that we were doing it in company.”

When sailing journalist Jimmy Cornell arrived in the Canaries in 1985 to interview skippers about their transatlantic preparations, it was this sense of camaraderie that drove him to organize a transatlantic event. Immediately embraced by cruisers and media alike, the ARC first cast off from Las Palmas in 1986 with 204 yachts representing 24 nations, making it the largest transatlantic crossing at the time and earning it a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records (a record that it later broke in 1999 with 237 boats, the largest race in the organization’s history. Since then more than 200 yachts have participated in the rally each year.)

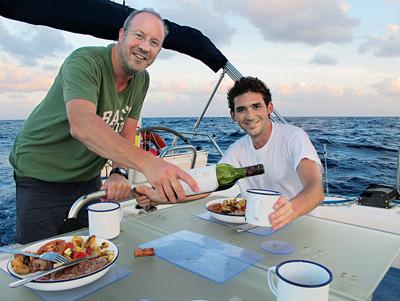

Our first day went by without incident—except for one lazy jack snapping during an early morning jibe, it was perfect. The winds stayed strong, and as we got farther out to sea, the waves subsided to 5 to 8 feet and we made good time. With one reef in our main and our genoa flying, we averaged 8 to 9 knots of boat speed. Ben made dinner, and, with Snark under the command of “George,” our autopilot, we sat around the saloon table and enjoyed our first homecooked meal. Ben, lucky for us, was a gourmet chef, and we instantly decided that he would cook and Dugald and I would clean. (For our celebratory halfway meal, Ben served foie gras to start, then confit de canard with broccoli and roasted potatoes for a main course, all complemented with a bottle of red wine.) Since I can’t make a peanut- butter sandwich, but am an excellent substitute for a dishwasher, I was happy with the arrangement.

On the morning of our third day the seas had calmed significantly, and it was time for someone to head up the mast to fix the lazy jacks. I was the lightest of the group, so I became the mast monkey. Going up a mast in the calm waters of a marina, a gentle wake can feel like a tsunami, and in an ocean swell—well, it is not for those afraid of heights, with a tendency toward motion sickness, or smart enough to talk their way out of it. Before I knew it, I was wearing a harness, dangling about 60 feet above the water, and clinging to the mast with my legs while the boat pitched beneath me.

On November 28th, we passed the 1,000-mile mark, entered other time zone, caught our first fish, and had our generator conk out. The next day, the sea and wind settled down for the first time, and we decided to fly our spinnaker. We had flown it briefly before, but high winds had kept us from using it much—now it seemed the best sail for the situation. Then, with one awkward wave and one gnarly gust, we wrapped the spinnaker around the forestay. Ben scrambled up to the bow and tried to fight the sail back around to unwrap it, but it didn’t work. We tried to turn head-to-wind to see if we could blow it back around—no such luck. The spinnaker beat itself against the forestay, lashing violently in the wind. After a lot of shouting, and a lot of pulling, we finally were able to get it down—first, partially into the water, and finally, onto the deck. As I watched it drop, I could see it was torn, its frayed ends flapping in the breeze. So, no generator and no spinnaker. We’d had, literally and figuratively, the wind knocked out of our sails.

Ben and Dugald lashed the chute down on the bow where it lay battered and beaten for the rest of the trip. Ben was determined, however, to fix the generator. Turning the engine on for one-hour blocks gave us some juice, but we were unable to keep a good charge. After a few days we tried one last option. Ben took the generator starter battery out of the lazarette and strapped it in place next to the engine starter battery beneath the saloon sole. Then he took two wires and connected the batteries, much like someone trying to jumpstart a car. The plan went off without a hitch, the battery charged, and afterward Ben hooked it back up to the generator and she turned over on the first try.

As the days came and went, we settled into life aboard, reading, trolling our fishing line, and checking our course. We began our routine of afternoon cocktails and games of Battleship, during which we traded quips about the Scottish Navy (“six rowboats with three tied to the dock,” as Dugald told me one day) and the “Mighty American War Machine.” Every time I was defeated (which was pretty often) there was a boisterous round of “Rule Britannia.” The smell of food from the galley mixed with the sweet salt air of the ocean, and dolphins and flying fish burst above the waves to entertain us. The winds tapered off for a few days, but for the most part, blew steady and true and the seas remained strong. We cruised along, the three of us taking our turns at the helm during the day and our watches by night. Reading, eating, talking, and enjoying each other’s company, we all experienced something we never had before: crossing the Atlantic under sail. There is a sense of freedom that comes with sailing the ocean that I don’t think can be duplicated—the gentle movement of the waves becomes the rhythm of life and the whisper of the wind in the sails, a gentle soundtrack.

Land Ho!

When I saw Martinique on the horizon, it was a barely discernible gray strip, looking something like a squall. It was the first piece of land I had seen in 16 days. Soon, we spotted St. Lucia off the port bow, and began to prepare for our arrival. With the sun setting, we cruised across the finish line at the entrance of Rodney Bay—2,794 nautical miles, 16 days, nine hours, six minutes, and 46 seconds after crossing the starting line off the coast of Las Palmas. We had crossed the Atlantic, 72nd of the 209 boats that completed the 2009 ARC. As we dropped our sails, we were met by World Cruising Club representatives who led us to our berth at IGY Rodney Bay, hopped out and caught our lines, and handed us each an ice-cold rum punch— welcome to St. Lucia.

That night we enjoyed food and drink with our fellow ARC participants as cheers rang out and horns blared to greet new arrivals. None of us aboard Snark had done any major offshore sailing trips prior to the ARC. We had pushed our comfort limit, and accomplished something that we had only dreamed about.

I don’t know if I’ll ever sail across an ocean again. I don’t know if I’ll ever again watch the sun rise off the port quarter while the moon sets off the starboard bow, or watch the plankton glow fluorescent in the waves, or stare for miles at nothing but the deep, dark ocean… But I do know this—in 2009 I had one of the greatest experiences of my life crossing the Atlantic Ocean with two amazing gentlemen and one terrific boat and, and I’ll never forget it.

As of this writing the ARC 2010 entry list is full, but adventurers seeking a solo berth aboard an ARC vessel should visit the World Cruising Club’s free Crewing Opportunities forum at www.worldcruising.com/forum/default.aspx. To sign up for the 2011 ARC, visit www.worldcruising.com/arc for the entry form and event details.