It takes a village, and a whole lot of prep work, to make a 201-foot 17-year-old mega-yacht like new in 180 days. The idea was simple, sort of. Find a yacht that fit the owners’ preferences and cruise the Mediterranean for the summer while planning a refit that would include hull paint; a redesigned interior; a Lloyds- and Cayman Islands-approved paperless bridge system; virtual acres of teak being stripped, sanded and varnished; seemingly miles of stainless steel being removed and polished; new marble soles and carpeting; updated furniture; and, well, the list goes on for many nautical miles. Oh, and the 2000 build had to be in and out of the shipyard between November and March. “We spent quite a long time looking for [a yacht] that suited the owners’ tastes,” Capt. Mike O’Neill says in an upbeat tone. “They like traditional yachts, and even ones on the used market in the five-year-old range have very contemporary designs.”

After about six months, the owners were reintroduced to the CRN-built New Sunrise, now Katharine, in France.

“They loved the boat, loved the interior and had chartered her previously,” O’Neill says.

American vendors flew across the pond to pitch the captain and owners on the project’s size and scope. In total, 28 South Florida-based contractors were selected for the refit. “All of the preplanning was a good four to five months” of work, O’Neill says.

With the 2017 Med season over, the captain and crew brought Katharine to the Rybovich yard in West Palm Peach, Florida. O’Neill says they chose the yard because of the dollar-to-euro exchange rate and lower U.S. labor costs. O’Neill and his team, as opposed to the yard, served as the project managers, a decision that saved another 15 to 20 percent on the overall refit cost.

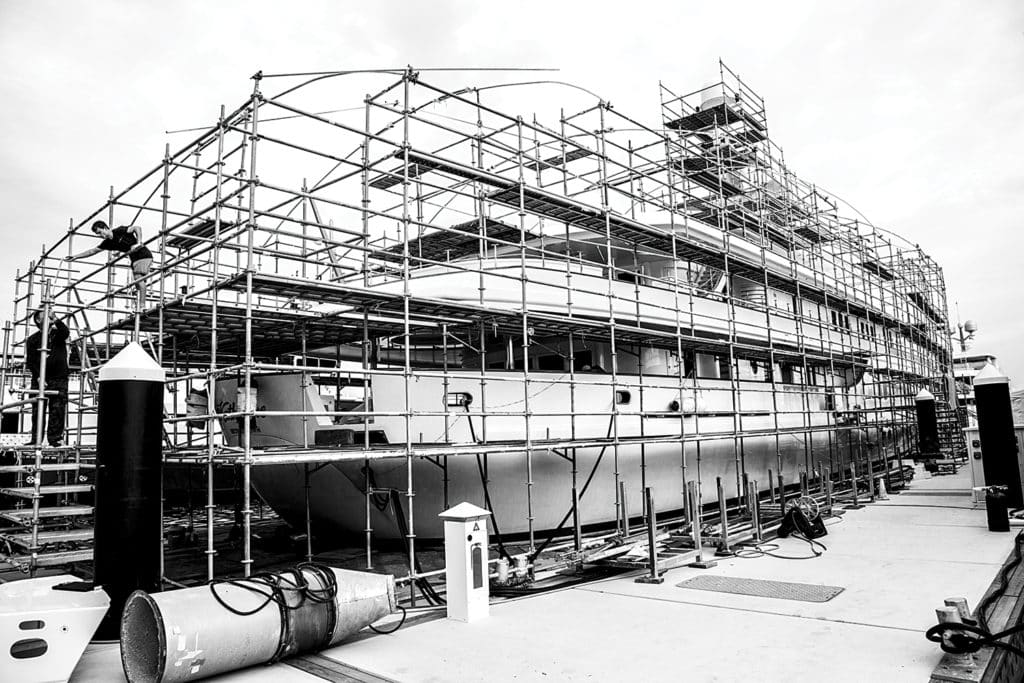

Katharine’s owners leased the yard space from Rybovich, which contributed engineering and dry dock services. O’Neill’s team set up offices on-site to stay on top of the myriad moving parts. The captain says his team was in the yard every day, except during the Christmas holiday, and worked six to seven days a week down the homestretch to make the March 31 deadline. Within the first day of arrival, scaffolding was going up, and within seven days, the 201-footer had been stripped with a tent over her.

There were other advantages to running the program too, O’Neill says: “We had a little more flexibility to make changes without having to wait for the shipyard.” One of those changes involved swapping out the lighting from halogen to LED on about 600 lights. “That was a project we thought would be easy at first,” O’Neill says, chuckling. But it also meant changing out around 200 transformers, because the halogens run on 110 volts and the LEDs need 12 volts. The lighting vendor was a 10-minute drive from the yard, a quick trip for O’Neill and his team. And in another turn of good fortune, the yacht’s original owner was an American, so Katharine’s electrical system was already spec’d for the States.

In addition to the quality of work that the South Florida vendors provided, their location was geographically pleasing for Katharine’s team. Travel time to the work site was short. If the schedule had to be adjusted on the fly, the change didn’t disrupt the timeline.

Efficiency was key. The captain gave each contractor a precise schedule. For example, the carpet company had an install date, but the marble soles had to be set before the carpets could go in. And before that, the soles needed to be made level. Everything had to happen lockstep, with a daily schedule for each task.

But this wasn’t the owners’ or O’Neill’s first refit rodeo. The team had performed a similar project on the owners’ previous yacht, a 131-foot Richmond. While it was a smaller vessel, the same rules applied. “We learned a lot from that project,” O’Neill says.

Something new on Katharine’s refit was what O’Neill called a “massive” bridge electronics upgrade. The captain and crew emptied the helm of multifunction displays, radars, VHF radios, automatic identification systems and more, and replaced everything with Furuno’s paperless bridge system. The setup is designed to run even in the event of power loss.

“We had to run new cables and new power supplies for the computer equipment,” O’Neill says. The tech is so cutting-edge, both the captain and the electronics installer flew out to Seattle to spend a few days training with the manufacturer.

With all the parts in place and the crew working long days those last weeks, Katharine splashed as a “like new” yacht by her in-water deadline. The project had gone only 4.5 percent over the original budget, a minimal overrun that O’Neill attributes to preplanning. “As these projects evolve, you always expect change orders, and we were very strict about what we could and could not add, but we built in a certain amount of contingencies.”

O’Neill says that if the owners and crew had the refit to do again, they’d do it the same way.

“It’s more work and more responsibility, but the financial gains were great, and we better met the owners’ expectations,” he says. “They ended up with the yacht of their dreams.”

Color by Numbers

Katharine’s painting, varnishing, welding and carpentry took five months and about 20,000 man-hours, according to Newmil Marine’s Sauer van den Berg, whose company performed that work. The paint job included using Awlcraft 2000 for the yacht’s superstructure and Awlgrip on the hull.

To ensure that all 201 feet of yacht had a mirrorlike finish, van den Berg’s team first checked the vessel for potential corrosion, and did repairs. All hardware was removed. Newmil Marine’s crew then tested for adhesion and wiped down all areas to be painted. The team also had to grind out blisters to bare metal. Anti-corrosive primers were applied. Epoxy primer, fairing and more primer came next. More epoxy primer was added to achieve the recommended “mil” thickness prior to adding the topcoats via sprayer.

The final touch was detailing and cleaning. TeamGantt chart software for project management helped keep the project flowing on schedule.