Down East in Nova Scotia, a fishing and sailing ship port thrives. Despite its 19th-century maritime roots, or perhaps because of them, Lunenburg has navigated into post-modern times with its place in the future firmly belayed.

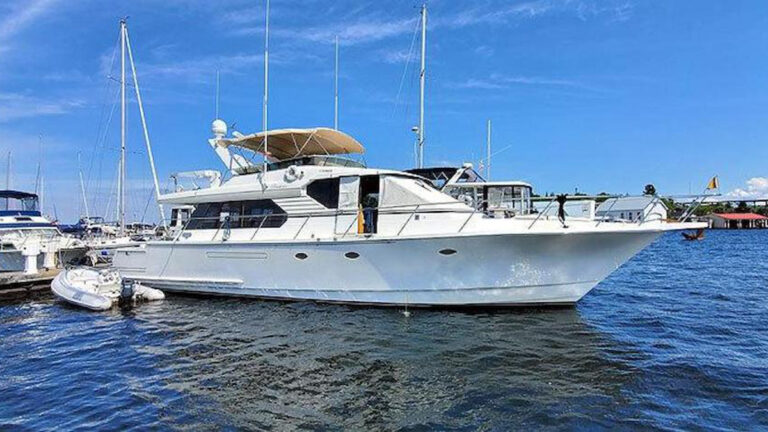

Landlubbers flock in to gawk at the old homes occupied by descendants of the first settlers. Ships under steam and sail come to get work done, and yachts find shelter off the waterfront. Atypical of a coastal town, this community of a little more than 2,000 has refused to sell its ocean views to the highest bidders. The town feels alive, authentic, friendly. Its citizens welcome visitors as expected admirers instead of seeing them through the eyes of a merchant desperate to make a sale. In 1995, a branch of the United Nations confirmed what Lunenburgers knew and named the port A World Heritage Site.

After we dumped four of our anchors at Thomas Walters and Son Marine Blacksmiths (founded in 1893) for fresh hot-dip galvanizing, we looked around the shop, dimly lit by the flaming forge. Sailing-ship iron fittings hung everywhere-cranse irons, deadeye straps, belaying pins the size of shotgun barrels, and anchors, big and small, of the fisherman type preferred locally on the rocky, kelpy bottoms of the Maritimes.

Greg Ernst, who apprenticed with the now-retired Vernon Walters, was the resident smith, and he looked the part. Taller than 6 feet, he had massive shoulders and arms. Only later did we learn he championed in the world’s “strongest man” contests. As we watched, Greg forged shackles that trawlers use when they drag for scallops, the last quarry after the cod fisheries died. Having pounded eye terminals into the white hot iron stock, he placed it into a bending jig and motioned for Nancy, my wife, to grab the lever. She twisted the iron rod into a shackle shape, grinning all the while. When my turn came, I had to use all of my weight to do it.

Today, the shop mostly makes custom-forged gear for local fishermen yet, relatively recently, produced the complete metalwork for locally built sailing ships. Just one of them, the replica of HMS Bounty built for MGM in 1960, required nine tons of iron fittings and hardware.

Vital in Colonial times, wooden shipbuilding peaked in the late 1800s. Two of the most prominent shipwrights joined hands in 1900, founding Smith and Rhuland, Ltd. This shipyard lasted until 1976 and launched 279 working vessels and 107 yachts. Consequently, the skilled carpenters in town find plenty of work on vessels returning for maintenance. Apart from Bounty, Smith and Rhuland built the replica of HMS Rose for the American 1976 bicentenary celebrations.

The most visible of their ships today is Bluenose II, a replica of a famous 1921 Grand Banks fishing schooner. Canadians revere the Bluenose. Drawn by amateur designer William J. Roue and captained by Lunenburg’s own Angus Walters, she beat all, except one, of the American challenges in the hot fishing schooner races of the 1920s and ’30s._ Bluenose II_ keeps a busy sailing schedule in Canadian waters and in the international Tall Ship events.

When she’s home, Bluenose II docks at the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic, a unique institution offering an in-depth look at the in-shore and offshore fisheries of the Canadian Maritimes. The museum, in the center of the Lunenburg waterfront, features a typical boatbuilding shop, a sail loft, rope- and net-making and whaling history, and has a display of early engines. Several smaller coastal vessels have found protection there, as have all the fishing implements employed, from trident spears and weirs to lobster traps and seines. The fishermen’s quarry of crustaceans, mollusks and fishes swim about in the aquariums.

Along the wharf, visitors can board the Theresa O’Connor, a 1938 auxiliary schooner and a good example of the last salt-bankers, which deployed their fishermen in dories. Cape Sable, another vessel moored there, is a diesel-powered trawler of the type that replaced the less-productive schooners. These trawlers dragged large nets on the sea floor. They eventually finished off the cod fisheries, causing what may be a near extinction of the species.

The waters off the Canadian Maritimes are cold, foggy and often stormy, and no display of the mute tools of the trade can adequately convey the painful toil of the early fishermen. Around the mid-1800s, the fisheries began expanding to the offshore waters in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Labrador. After a successful foray onto the banks of Newfoundland in the 1870s, the Lunenburg fisheries boomed.

Large, between 100 and 150 feet on deck, Lunenburg-built schooners modeled on fast New England designs entered the increasingly competitive trade. A fishing season began in the freezing weather of late March on the banks off Sable Island. Six weeks later, after unloading in Lunenburg, schooners sailed to Newfoundland. Fishing there till the end of September, they were prey to the deadly storms resulting from the coupling of hurricanes with northern depressions. During the August storms of 1926 and 1927, six Lunenburg schooners went down with 138 men.

Most fishermen, however, lost their lives from dories, small open boats launched from the schooners with a crew of two men setting out baited lines. Without modern weather forecasts, aids to navigation or means of communication beyond a trumpet-style foghorn, hundreds of men drowned, starved or froze when they became separated from their ships for too long. The Fishermen’s Memorial, a striking Stonehenge-like assembly of tall black marble pillars, lists about 600 names of men lost at sea up to 1995. Read the names and you realize a stormy fishing season often wiped out all the males in a family.

In spite of the losses, the dory was the most important tool of the fisheries in the past. It is remarkably seaworthy when it’s loaded, and is simple and economical to build. The design survives today as a pleasure boat.

During our wanderings through Lunenburg’s waterfront, we came to The Dory Shop, where Nathan and Morgan Smith built all kinds of dories from 5 to 20 feet, classed traditionally by the length on the bottom. We needed new extra-long oars for our dinghy, so the Smith brothers directed us to Milton Fancy & Sons, the oarmakers. Should we need traditional lignum vitae blocks, we could have gone to Arthur Dauphinee & Sons.

Of course, the venerable Lunenburg Foundry could sell us one of its iron ship stove/heaters, or an anchor windlass for any size anchor, or a ship’s bell fit for a sloop or destroyer. Three sailmakers in town produce sails, from traditional square flax spankers to exotic racing composites. Should our ship threaten to sink, we could have taken her to the Lunenburg Industrial Foundry and Engineering yard, which hauls out small ships and megayachts on a Synchrolift and smaller craft with a Travelift.

When you add all the welding and engineering services available, Lunenburg could easily outfit or refit almost any craft, sail or power, up to a few thousand tons displacement.

Strange as this may seem, this paragon of maritime history began as a farming community of Protestant, mostly Lutheran, refugees from persecution in parts of Germany and Switzerland. In the 1750s, British authorities in Halifax sought to out-colonize the French Acadians scattered in Nova Scotia and brought nearly 1,500 so-called “Foreign Protestants” to Merligash Bay, now Lunenburg (named after King George II’s German Dukedom). These hard-working people must have become prosperous within a few decades because in 1783, six privateer ships from Boston invaded and put the town successfully to ransom. By 1830, the town merchants had developed a profitable economy, based on trading dried codfish in the West Indies (where it fed the plantation slaves) for sugar, molasses and rum.

The interesting architecture in the Old Town part of Lunenburg reflects the growing wealth of the community from the late 1700s through the 1800s. Most houses sport the so-called Lunenburg “bump” or “bulge,” a five-side dormer extending over the doors. Ship carpenters often got involved in house construction, contributing to the longevity of the homes. Unable to attach fancy adornments to their utilitarian everyday ships, the shipwrights vented their creative powers when they built churches. The oldest church in town, St. John’s Anglican, which has undergone several renovations, perhaps best exemplifies this Carpenter’s Gothic Style. For us, it embodies the temper and spirit of Lunenburg’s founders.

It is easy to navigate the Old Town. Laid out by 18th-century British Army planners, the grid plan is identical to another of their creations in the deep south of the North American seaboard, the port town of Savannah. During our three visits, we stayed longer than planned. Cozy cafés kept us nourished, and the weekly farmer’s market filled our ship’s lockers.

Sailing into the port, however, calls for careful piloting. Bluenose II draws 16 feet and gets in without trouble, but the buoys marking several scattered shoals can be confusing. Chart 4328 published by the Canadian Hydrographic Service clears all doubts, showing deep waters running to the tall outlying islands that are impossible to miss, even in foggy conditions.