I always knew the Leeward Islands were fabulous for their beaches, but until I visited Nevis and St. Kitts, I did not know what other riches they had to offer. That must be why expedition-style yachts were invented: to satisfy roving spirits like mine, with a 12-knot moveable feast.

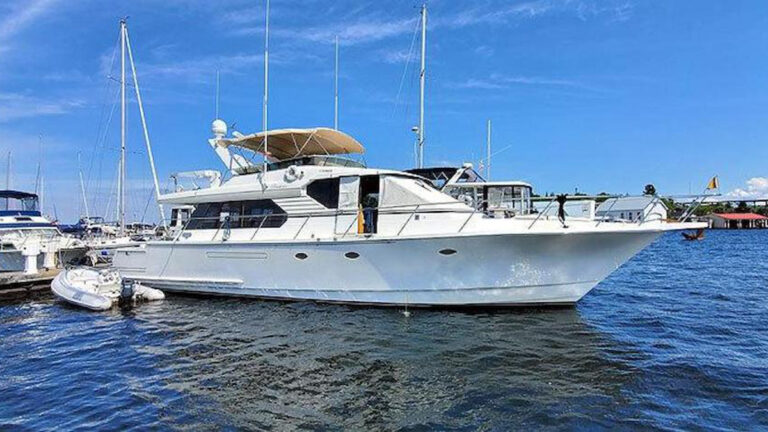

Sitting high and proud on the turquoise water, the 90-foot Doggersbank Tivoli was a pleasing sight. I liked her jaunty bow and sweeping deck, the saloon’s six wraparound windows and rich sapele mahogany. She has the stowage and fuel capacity to go anywhere in the world, and her owner is willing to do just that.

A lifelong sailor, Tivoli‘s owner had commissioned Vripack’s Dick Boon to design an aluminum-and-steel powerhouse with separate crew quarters, superyacht amenities for six guests and a range of 6,000 miles. When I met him in Antigua, Tivoli had four wide-open days before she repositioned. Where did I want to go?

In the late 1780s, British Naval Admiral Horatio Nelson courted Frances Nisbet on our very passage, a smooth, six-hour ride over the churning deep. In Nelson’s day, Nevis and neighboring St. Kitts were the first names in the Leewards, the richest, most productive spots on Earth. How often Nelson must have admired Nevis Peak, with its head lost in bouffant clouds. I imagine he furled sail off Fort Ashby and watered at a nearby spring. Those aboard today’s superyachts seem to prefer Pinney’s Beach, where flags stream from Sunshine’s, a celebrated watering hole.

Sunshine’s signature potion, the Killer Bee, includes an elephant shot of rum. That was my initiation to Nevis. If golf were my game, I might have kicked off my visit at the Robert Trent Jones-designed golf course at the Four Seasons Resort.

Charlestown, a few minutes away by tender, has cheerful colonial facades and a museum in the childhood home of Alexander Hamilton, making it one of the sweetest Caribbean capitals. Hand-churned lemon ice cream, on tap at the waterside spot Gallipot, may be the hemisphere’s best. Meanwhile, Connecticut ex-pat Barbara Whitman, who has a master’s degree in marine biology, showed snorkelers the underwater world off Oualie Beach.

Ordinarily, that might be all a charter guest would want to see of this 36-square-mile island, but Captain Richard Collingridge, who knows the Leewards well from his previous watch on Mirabella III, had other ideas. The beauty of Nevis and St. Kitts is not just on the beach; it is in the islands’ history, architecture and humanity. For that, Collingridge said, I should venture inland.

A pixie redhead with a VHF and van presented herself.

“T.C., darling,” she said by way of introduction. “Stands for tough cookie. No one’s called me Thelma Claxon in years.”

In a previous life, T.C. drove a double-decker bus in London. Now, she seems to know everyone on Nevis: the Carib artisans who helped create Fothergills, a recreation of a historical village; a landscaper at the Botanical Gardens who was familiar with the genealogy of every orchid (and even slipped me some ylang-ylang seeds); and the archaeologist-historian David Rollinson, who led me through the rubble of New River, a former sugar plantation, where the dust of Carib and colonial civilizations now mingles.

Nevis was once the queen of England’s colonies, T.C. said, and people have attended to it with appropriate care. The Caribbean’s last wood great house, for instance, was in good repair at Hermitage Plantation. Montpelier Plantation, where Nelson married Nisbet in 1787, had been refurbished, and restorations were also underway at Cottle Church on Round Hill Estate and the colonial Bath Hotel.

I returned to Tivoli exhausted and melted into her shaded after settee. Richard Broadhurst, or Broddie, our self-taught Australian chef, had been working on an invention made from king prawns, pink grapefruit, dates, mint, coriander and coconut crème mousse-and that was just for the entrée.

“Buy the freshest, choicest ingredients, and do as little as possible to keep from mucking them up,” he said, summing up his philosophy. Fusing flavors and textures so engrossed him that he forgot to name the finished dish.

Once we’d gathered around the dining table, which was scenically lit with LightTouch controls, stewardess Kate Craggs, who has a 200-ton captain’s license, recited a litany of foods that was a culinary syntax all its own. Collingridge deserves credit for assembling a terrific crew.

I spent my last hours on Nevis at Golden Rock Plantation with owner Pam Barry, who also manages the inn. Golden Rock, once Nevis’ wealthiest sugar estate, is now an idyll of mill ruins and jungled footpaths patrolled by vervet monkeys. Barry and I sat in the outdoor gardens and talked of racehorses, silk cotton trees and her ancestor, Edward Huggins, who in the early 1800s founded the site.

My time at Golden Rock Plantation evoked everything that is striking about Nevis. Some places we visit only once. As Tivoli made the three-mile trip across the Narrows to St. Kitts, I knew I’d someday return.

The name of our next anchorage, Ballast Bay, speaks for itself. A dive team that arrived ahead of us came across a British troop ship decked with 13 cannons. Break out the tanks (Tivoli carries eight, plus two compressors), for somewhere off St. Kitts lie 400 others, the wreckage of a struggle for England’s Caribbean possessions that helped the United States win the Revolutionary War.

It is easy to see why the Caribs called St. Kitts Liamuiga, or “fertile land. The island is a rich landscape of contrasts. The north sustains one of the world’s few growing rainforests, while the south, where yachts anchor, is an arid reserve of amber hills and salt flats crusted over like snow. Perched high on the sundeck with a cocktail, I watched the sun dip behind Mt. Liamuiga and eclipse the moon. Could there be a more perfect remove from civilization? Bathed in the soft lights and music of our yacht as the capital city of Basseterre twinkled from afar, I thought not.

The blue coves of St. Kitts were perfect for kayaks and water skis, while on shore the empty road begged for the motorbikes Tivoli keeps on board. As on Nevis, the defining experiences of St. Kitts lay elsewhere.

One of them, the National Museum in Basseterre’s former treasury building, stood before me as I stepped from Tivoli‘s open stern onto the wharf at Port Zante. The museum is worth seeing, especially if Jacqueline Cramer-Armony is there to make the bloody Kittitian saga come alive. Cramer-Armony is executive director of the St. Christopher Heritage Society, a group spearheading an effort to preserve the area’s historical infrastructure.

Basseterre is a perfect walking city, with harmonious squares and fine period structures. Larger and statelier than most American town greens, Independence Square, where slaves were once sold, was full of pedestrians who passed with a smile and hello.

Residents of St. Kitts are sociable. A retired boxer named Hurricane shadowboxed for me on a rooftop. From the balcony of the Circus Grill, which overlooks a courtyard modeled on London’s Picadilly Circus, one patron (the director of the Organization of American States, as it turned out) shouted and offered me a drink.

Another site on St. Kitts that shouldn’t be missed is Brimstone Hill, a former military fortress. To survey its barriers and bastions, mounted 750 feet above the ocean on more than 40 acres of land, is to know why some call it the Gibraltar of the West Indies.

From its lookouts I counted four distant islands (you can see six on a clear day). Mounted around the citadel, cannons pointed in all directions to the mountain and sea. The feat of digging and cutting those thousands of rocks, quarrying the limestone and joining them with mortar from a continuous kiln took my breath away.

Did I know that the United States’ last battle for independence was fought in the Caribbean? Art Keusch, owner of Ottley’s Plantation Inn, entertained me with such facts on his majestic grounds. In those days, said Keusch, an American flag in the Leewards was so incendiary that Admiral Rodney cannoned an entire seaport for saluting one. Fortunately, the Keusch family was far friendlier, inviting me to their famous Sunday champagne brunch.

But it was dessert night aboard Tivoli. A chronic dieter, I had given in to our last supper a ginger-and-brown-sugar parfait with banana-and-rum coulis. As Broddie would say: If you’re going to indulge, do it sinfully.

Cruising with Tivoli‘s owner was an instructive experience. After all, who knows the yacht’s virtues and peccadilloes better than he does? Her systems, from the dash to gensets, met my offshore expectations, while the decks and crew quarters, each with an en suite head, surpassed those of some larger yachts. My stateroom provided every comfort, including the best sleep I’ve known on land or sea (thanks in part to Daly Brothers bedding). The owner’s suite, with steam shower as well as whirlpool bath, had more than its share. With her second laundry room, flying bridge full of toys and three dining venues, Tivoli seemed to have everything (with the possible exception of an outdoor stair leading directly from the sea to the sundeck’s pool).

When we parted company in Port Zante, Tivoli was headed for St. Martin and then Newport, Rhode Island, for her American debut.

“Where will you be chartering?” I asked the owner.

“New England and Canada this summer,” he said, “and the Caribbean next year”. Then he reconsidered. “But if someone asks for Turkey, we’ll leave tomorrow.”

Wherever the spirit moves her, Tivoli is good to go.

Contact: Nicholson Yacht Charters, (401) 849-0344; antigua@nicholsonyachts.com; www.nicholsonyachts.com. Tivoli charters for $29,500 per week, plus expenses.