The anchor-up bell tolled on the bow, and Esmeralda headed seaward through the green waters of Simpson Bay, Dutch Sint Maarten. Out in the open, the yacht began slicing through an ocean riled into a white-capped frenzy by a 25-knot trade wind-a frequent winter visitor in the Caribbean. Twelve-foot seas came in close ranks, but failed to disturb Esmeralda’s 202 feet of steel. Only sheets of spray drumming against the bridge windows and then smoking over the sundeck above testified to how rough the ocean had turned.

We congratulated ourselves on the decision to spend the whole of our cruise on St. Barts, whose pinnacles gradually gained substance under a sky brushed into cold cobalt blue by the wind and brilliant sun. Among the other interesting islands in the vicinity, Anguilla, Saba and Statia, only St. Barts offers good shelter when the Caribbean swings to such wild winter weather.

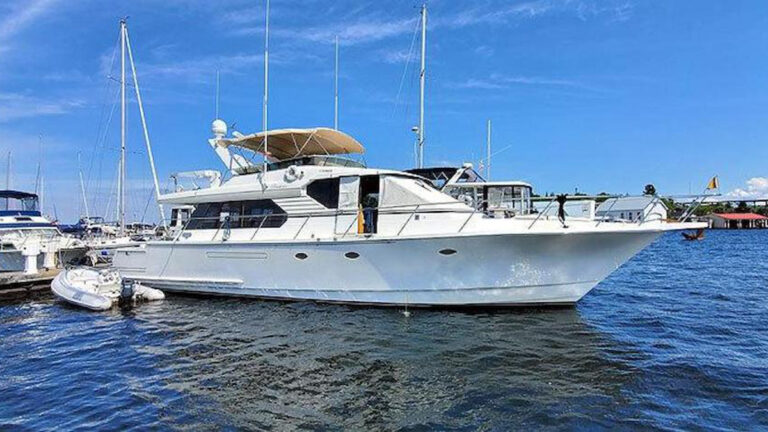

As we approached, several yachts, the largest about 170 feet, tugged at stern hawsers along Quai General de Gaulle in Gustavia, the inner harbor of St. Barts. Esmeralda, which draws 15 feet, cannot enter because her overall length exceeds the maximum allowed inside. So we anchored in the outer harbor, which was smooth in the strong wind.

St. Barts towers over the ocean with its nearly 1,000-foot-high Morne Vitet, but at eight square miles claims little of the Earth’s surface. Named centuries ago after Barthelemy Colombo, Christopher’s brother, the island entered global consciousness when more recent seascape explorers, the Rothschilds and a Rockefeller, bought land here. This ended the rural lifestyle imported by austere 17th-century colonists from the Atlantic coasts of France whose women wore Quichennotte, the kiss-me-not headgear shaped like American mailboxes.

Today on St. Barts, everybody kisses somebody several times a day, just like in Paris. The island’s metamorphosis into a mecca for posh vacationing revived it, as its flat land and shortage of fresh water could not support even basic farming. During the early colonial days, the economy was based on the good harbor, which enjoyed free-port status as early as 1749. St. Barts, always a French island at heart, often changed administrators: the Knights of Malta, the West Indian Co. and, for 80 years, the Swedes, hence the harbor named after King Gustav III.

Wondering whether such a tiny place could keep us entertained for several days, we settled down for lunch at the round table of varnished teak on Esmeralda’s very stern, the lowest deck out of four. It opened onto a busy nautical scene complete with sailing ships anchored near small peaked islets.

While our captain was ashore clearing French customs, we fell under the jurisdiction of Susan Sawers, the chief stewardess. A bundle of energy, she talks with a Gallic flair and a rolling Scots brogue. Susan learned her wines when working in France. We quickly learned to leave the pick of labels to her.

Esmeralda can host 22 guests and commits 19 crew to pamper them. There are enough sailors to run four tenders at the same time, so some guests can do water sports while others explore on land. Besides the English core of eight, the crew represents Croatia, ex-Soviet Georgia, the Philippines, Jordan, Serbia, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. Among them they speak 12 languages. This is a cultural asset because Esmeralda’s typical clients, large families, hail from many backgrounds: Royal Saudis, Americans, even the new Russian oligarchy.

The head chef, Andy Fleming, a tall, slim, soft-spoken Scot, has a handshake like a Highland chieftain. The main course he crafted for lunch our first day was pure food art. Four petal-like prawns surrounded the centerpiece: a wreath of fettuccini woven around a spathe of lobster wrapped in tissue-thin salmon. The pasta would delight a Sicilian, while the salmon lent a whiff of brine to the purity of lobster.

On our first adventure ashore in Gustavia, we found a whirlwind of tiny vehicles in narrow streets riddled with potholes. Young French women on scooters blossomed in the traffic. After asking for directions (most locals speak English), we rode out of town. Our rented Jeep proved its mettle on the old roads battered by the previous hurricane season. The palm crowns looked oddly like MTV kids, with new top shoots rising from downcast broken fronds. We climbed to a view of red roofs and blue ocean, then down again to a valley of ancient salt ponds.

A path through the dunes led us to Anse de Grand Saline, a scallop of a beach defined by headlands. No hotels or beach bars there. A wild wind whistled across the surf, and we joined other happy souls floundering in the swirling waters of spent waves. Though it was the height of the winter season, there were just a few dozen people around.

We continued to explore the coasts, poking into Anse de Petit Cul de Sac, Anse de Grand Cul de Sac, Anse de Marigot, Anse de Lorient and Anse de Flamands. There are enough bays on St. Barts to accommodate every sun freak, boardsailor, surfer and Jet Ski maniac while still leaving miles of space. Even at Baie de St. Jean, a village of bistros, galleries and boutiques that challenge the shopping in Gustavia, just a few couples dotted the sweep of the beach.

The shores of St. Barts are not just about swimming and tanning. Many of the island’s 50 restaurants have staked out scenic spots along the coast. As sampling good food is an essential part of roughing it in a Jeep, we had one lunch at Anse des Cayes, a gleaming beach and foaming seas framed between sheer promontories. Cresting waves marched by the windows in the restaurant Quanalao (the Arawak name of the island, which means pelicans). We savored lobster gaspacho and salmon carpaccio while entertained by a lone, wave-dancing surfer. Gilles Bertaud, a master chef from Curnonsky Academy, had recently won first prize at the Fete de Gourmand, which each May brings restaurateurs and vintners from France. Monsieur Guy Roy, the owner, joined our table.

Much of the development on the island is fairly recent, but a good bit of old St. Barts remains. Driving to Anse de Grand Fond, we paralleled a high ridge of wildly tangled native forest, green and inaccessible with barbicans of pink rocks overhanging precipices. The Jeep then leveled out along a hill of waving golden grasses crosshatched by walls of weathered coral. Delivered by the ceaseless pounding of Atlantic rollers, chunks of coral lined the seaward edge of our coastal road.

Sticking so far out into the ocean, the island attracts pelagic life. In 1999, St. Barts set aside a dozen islets for fish and birds, and three beaches for nesting turtles.

You’d never guess, but Esmeralda is named after a famous reptile. Destined to become sailor’s food, he escaped ashore from a ship wrecked in the Seychelles in 1808. Named Esmerelda, the tortoise now weighs 705 lb. at age 206. The yacht’s owner finances the Cypress-based CYMPPA, an environmental group working under a logo of a stylized Esmerelda to clean Mediterranean shores and preserve sea turtles.

On Esmeralda, we dined at three levels, literally. The stern was my favorite for an early meal when the red sun plummeted into the western ocean. For formal dinners, we gathered inside attended by fluttering stewardesses. When buffet dining on the bridge, we enjoyed two spectacular views: the islands around us and the arrangement of platters on an Epicurean altar that included whole poached salmon in cucumber aspic, reclining Maine lobsters and pagodas of tropical fruit under a vase of fresh lilies.

Once, like overindulged profligates, we decided to see whether Gustavia’s culinary efforts could measure up. We arrived by yacht tender at the wharf of La Route de Bucaniers. Styled like an open port tavern, the restaurant faces the harbor lights. We found the wines excellent, rather a rule because most establishments maintain extensive cellars. Young wines, which travel best, arrive each year and are stored until maturity. Apart from the continental French, the menu offered creole dishes. I went for a lambi (Queen conch) appetizer wrapped in pastry, a French version of the earthy Bahamian conch fritter. The delivery of my entrée, octopus tentacle tips, was a professional ritual. Again the food had a distinct French flavor, different from Iberian octopus cookery. Later, we popped into Le Select, a popular bar begun by Marius Stakelborough, St. Barts original, as the French say.

At dawn of my last day aboard, I sauntered onto the jacuzzi deck above the bridge. Wind-torn clouds streaked across the sun’s glow rising behind the hills of Gustavia. Two brown boobies, streamlined seabirds of the tropics, hovered at face level an arm’s length away, their heads moving slightly, one eye on the water and one on me. Suddenly, they folded wings and divebombed a squid lurking near the hull.

As the yacht headed back to Sint Maarten, I joined Capt. Michael in the wheelhouse. He maneuvered with variable-pitch propellers and a tiny aircraft wheel while keeping an eye on a television screen, which let him monitor the engineroom and the deck crew tying down the small boats. The weather seemed even rougher, but thanks to gyro-coordinated stabilizers, Esmeralda tracked on an even keel. Behind her helm is a plaque of the yacht’s 1981 launching at Codecasa yard in Viareggio, Italy.

With the present ownership, the yacht has reached peak form: sleek outside and elegant inside. Michael, who has run large yachts, passenger vessels and even salvage ships, has a practical vision of a proper ocean yacht. He also has practiced as an interior designer in England, and he helped with the yacht’s accommodations. My Tobago suite sported burled South American lupo wood paneling with a desk and huge hanging wardrobe. The bedroom was connected to a cabin of matching sunny design where I could do some work. All brass work in the marble bathroom was plated with gold.

Simpson Bay on Sint Maarten was choppier than before, but Esmeralda’s size let her ride easily. Boarding the tenders could be wet, but Michael used the bow thruster to swing one side into a lee and we stepped in with dry feet. n

Contact: Yachting Partners International Ltd., (011) 33 493 34 01 00; fax (011) 33 493 34 20 40; ypifr@ypi.co.uk; or any charter broker. Esmeralda charters for $154,000 a week plus expenses for events, and $119,000 otherwise.