From aboard the Fleming 75 Nikita, I spy what looks like a miniature cable car. It starts at the dock and travels up — and up, and up, at least 500 feet — to a home high above Norway’s Geirangerfjorden fjord. Geirangerfjorden. It’s OK that I can’t say it, because I’m pretty much speechless looking at the fjord’s beauty. That home is along a shoreline that is a collage of forested slopes, towering cliffs, waterfalls, pastures and isolated farmsteads, some of which are built atop impossibly high, verdant plateaus. How the residents access them, or how building supplies were lofted up to these precipices before the days of cable cars, remains a mystery to me. One of the now-dormant hydroelectric stations here, Flørli, holds two world records: the second-highest fall, with a distance from reservoir to turbine of nearly half a mile, and the most steps, at 4,444. We’re happy to look up at that one from the yacht too.

Norway is known for many things, from snow-capped mountains to enchanting villages, but it’s best known for its fjords and out islands, which rank as some of the world’s most picturesque and easily accessible. Most are within protected waters, and passages between destinations rarely require more than a day’s cruise, making this region a playground for cruisers who want to commune with nature.

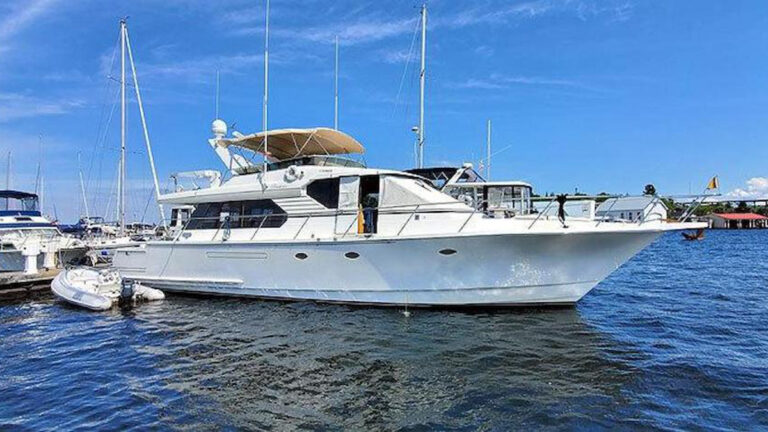

During a three-week passage aboard the Fleming 75 Nikita, our five-person crew made 17 stops along Norway’s southern, fjord-bound coastline. Geirangerfjorden, among the best-known fjords in Norway, is part of a larger fjord network that includes Storfjorden, Norddalsfjorden, Tafjorden and Sunnylvsfjorden. It penetrates deep into Norway’s vertiginous interior, which will have to wait for another day, since the coastline itself offers so much to see.

After being underway for a half day, we reach the village of Geiranger, situated at the head of the eponymous fjord. The village seems quiet, albeit with a substantial marina, by Norway’s standards, filled mostly with family-size powerboats for day cruising. I trek up the dock and make a circuit around the village, which, the locals warn, goes from sleepy to frenetic each morning as one to three cruise ships disgorge thousands of tourists.

The following day it happens, but it’s a passing storm instead of a flood; most of the visitors board buses for day tours, leaving the hiking trails deserted for us. Nikita’s mate and I travel to a farmstead roughly 1,000 feet above the fjord and drink in the storybook vistas.

A confession: When Nikita’s owner suggested that we stay off the boat and visit the Flor & Fjære garden, I was less than enthused. I’m not sure what I imagined a visit to a private family estate with tens of thousands of flowers might be like, although I was certain it would be boring compared to what we’d see in nature.

I had no idea how wrong I could be. Situated on the island of Sør-Hidle, this horticultural miracle defies logic. There are roses and banzai trees, cactuses and windmill palms, and each garden contains exotic plants from all around the world, with each display offset by lakes, bridges and waterfalls. A herd of sheep, fenced off from the gardens, is here too, along with a sandy beach that can be mistaken for a secluded tropical island. The variety of plants and trees is astonishing, particularly when one considers the latitude at which it resides, similar to that of Stockholm, Sweden, and Helsinki, Finland.

Flor & Fjære founders Åsmund and Else Marie Bryn, in 1965, built a cottage on the island as a getaway from the Norwegian city of Stavanger, where they ran a commercial nursery. Åsmund became bored and planted a garden. By 1995, the barren, windswept island retreat was transformed into a veritable Garden of Eden with its own microclimate. That same year, the couple’s son opened the garden to the public. Last year, more than 28,000 people reportedly toured the grounds. Like many of them, at the end of my visit, I vowed to return.

But on this journey, I still had more to see. From ashore at Preikestolen, known as “Pulpit Rock,” I could stand on a precipice and gaze down at Lysefjorden nearly 2,000 feet below. Gray clouds hung around snow-speckled peaks, but the weather was clear enough to see a dozen miles up the fjord. In a few hours, the tourists would be cheek by jowl in this spot, but by then, I’d be back aboard Nikita, with my eyes on some other of nature’s prizes.

Floating History

While Nikita is berthed in the oil industry port of Stavanger, I feel as much as hear a distinctive sound, a rhythmic kachug, kachug, kachug. Looking out the salon window, I see a vintage fishing boat blowing smoke rings from its obsidian stack, giving the vessel away as the home of a single-cylinder diesel. I beeline it to the bulkhead, and the vessel’s mate — with his “crush cap,” striped epaulets and perfectly manicured beard — takes me down into the engine room to behold the behemoth chugging away at 200 rpm. Each time the cylinder fires, it shakes the vessel to the top of the mast. The air smells deliciously of hot oil. It turns out that this is the MS Rapp, built in 1913 out of Norwegian cedar and repowered in 1955 using what’s popularly known as a 40 HK RUBB, which was manufactured by Wichmann Motorfabrikk at Rubbestadneset on Bømlo, an island just south of Bergen.

Power Principle

Most of the wharfs we visited offered meager electrical hookups, typically between 8 and 16 amps at 240 volts (1,920 to 3,840 watts). This shortage could have been challenging, if not for the setup on board Nikita. She has a 2,000 amp-hour lithium iron phosphate battery bank and a 16 kW power-sharing Victron inverter/charger system. Basically, the entire vessel, including air conditioning and the galley stove, can operate from the system.

There are other benefits too: After 19 hours of quiet ship time, with no shore power or generator operation, Nikita’s battery bank was still at 50 percent. Unlike conventional batteries, these batteries can be depleted to 20 percent, and less-than-complete recharges don’t harm the batteries. Using her twin 400-amp alternators, Nikita recharged the 50 percent batteries back to full while underway in just three hours.

Ålesund’s Shetland Bus

During World War II, the Norwegian town of Ålesund was nicknamed “Little London” for the resistance activity that took place in and around it, along with the frequent, small-boat crossings known as the Shetland Bus made between the town and Scotland’s Shetland Islands. Early in the war, all of the crossings carrying resistance fighters, saboteurs and agents, as well as supplies and refugees, were made using local fishing boats known as Møre Cutters, which were unique to Ålesund.

The wooden boats were 50 to 70 feet in length, with twin masts and a single-cylinder semidiesel engine. Most crossings were made in winter, which afforded the camouflage of long, dark nights, but also subjected the boats to North Sea gales. A number of the vessels and their crews were lost to enemy action or bad weather. A respite arrived thanks to the U.S. Navy, which, in 1943, provided four 110-foot former submarine chasers. They were faster and safer than the fishing vessels, and all survived the war.