Crazy Capers of the Caribbean Charter Fleet

Yacht chartering in the West Indies has become “big business.” Anyone who wants to cruise the Caribbean has only to contact a yacht broker or agent, hop a jet and make a half-day switch from anywhere in North America to his privately chartered vessel. Upon arrival, he can be reasonably sure that the boat will be well found and professionally operated in a reliable manner.

All this has happened in the last 15 years. Before then, you had to be on your own to cruise the area after sailing or shipping your own boat there, and it was such a rare feat that you usually wrote a book about it and everyone envied you.

In the early 1950s however, various factors began to combine to bring about the situation we have today. Yacht chartering started in a modest way, and the beginnings were pretty colorful. Some of the early adventures have become a part of the modern legends of the Caribbean, and, even though today’s operators are mainly reliable businessmen, they aren’t exactly the gray-flannel-suit-and-Homberg type yet. Local color is far from dead.

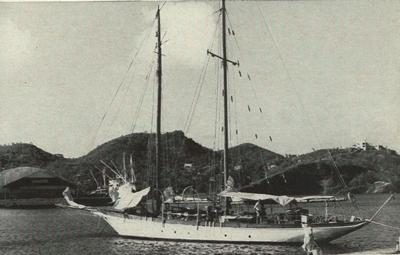

The first of the factors that started the development of the charter business was the advent of Commander V.E.B. Nicholson and family. Retired from the Royal Navy after World War II, he purchased the venerable schooner Mollihawk and was on his way around the world with his wife and two sons when they casually happened into English Harbour, the abandoned Royal Navy Dockyard at Antigua, planning to do some work on Mollihawk.

One thing led to another, and the Nicholsons ended up in the charter business while helping to launch the Friends of English Harbour organization which has to a large extent renovated and restored the old Dockyard. They now have a travel agency, are agents for a large fleet of charter boats, and operate a marine store, radio station and hotel. This can happen if you are a charming Irishman with two strong, charming Irish sons.

The second factor could be found northwest of Antigua at St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, with its incomparable harbor and good air connections. Until about 1950 or so there were no charter yachts there, but circumstances conspired to change this situation. At that time, St. Thomas was a divorce mill. There was nothing to do on the island and no way to get to St. John, or to the other Lesser Antilles. Air communication was then minimal and the island was overloaded with wealthy, bored would-be divorcees with nothing to do and no place to go.

This was the situation when the first of the post-war escapists began to wander down into the Caribbean in sailboats. With few exceptions, the skippers of these first yachts to cruise the islands in the late forties and early fifties were young, adventurous, single, often good-looking and always broke. What to do to raise money? The most obvious course of action was to take the rich, bored ladies of St. Thomas out for a sail to St. John’s wonderful, deserted beaches.

From such informal beginnings, the combination of adventurous young men who needed a buck and a retired Commander RN who wanted to repair his yacht has created a business that has done much to raise the standard of living in the islands, and add to the tourist explosion that now exists.

Today, the charter business is often entered into by a married couple that has chucked life in the States, sold everything, and is trying to make a go of it in the islands. In some cases owners send their yachts down with a skipper and charter her out when they aren’t using her, to minimize their expenses. This is all to the good for charter parties. Boats are better kept and crews more reliable, and amenities of life such as food in variety, fresh water, showers, ice in your drink and engines that run, are there for the asking.

But to go back; as I said, it must be admitted that some of the pioneer characters were amusing and colorful in the extreme; for instance, Roger and Al, both very athletic and good-looking, plus excellent as raconteurs and great on the bongo drums. Each evening after returning from the charter they would go to the Virgin Isle Hotel to drum up trade and book the next day’s customers, usually for the day trip to St. John.

First as they sailed out of the harbor, Roger or Al would entertain the gals by standing on the end of the bowsprit and with the spinnaker halyard in his hands, swing off to leeward and come in over the stern pulpit. It was a great performance and the charters loved it. Then, once clear of the harbor, it was off with all the clothes. “What, you have never been sailing before? Well, everyone takes their clothes off when sailing in the tropics.” It was quite a sight, two men and six to 10 gals with not a stitch of clothes among them, and, wow, the sunburns.

In the old days, the charter fleet came from local craft that had been hurriedly converted to charter boats. A two-burner primus sufficed for cooking. A small deck icebox provided ice for three or four days, and after that you drank your rum neat and your beer warm. Water supply was meager. One boat had a pump so small, six strokes filled a water glass. There were no showers (except in a squall), minimal electric lighting … and it was a big event when you saw another yacht.

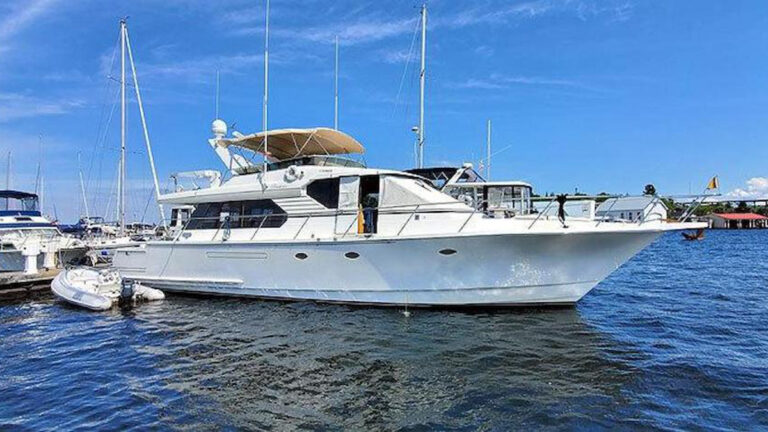

Things have now changed; boats are specifically built for chartering with huge water tanks, hot and cold running water, showers, and fancy stoves, some even have air conditioning, huge generators, piped hi-fi, white-coated stewards, cordon bleu cooking with vintage wines and champagne, and large launches for water skiing. The deserted West Indian anchorage is pretty much a thing of the past. The luxury yachts have every comfort, but they are usually motorsailers more dependent on their engines than their sails. It is still possible, though, to find a boat that is plain, comfortable and a good sailer, if specifically requested from charter brokers.

Today instead of deserted anchorages one almost always finds another yacht or two. This can be pleasant and sometimes congenial except for large generators. A really good charter skipper not only knows what boats have generators but knows which side of the boat it is mounted on, and he does his best to anchor on the opposite side from the generator exhaust. West Indian anchorages also even have water skiers now.

In years gone by many of the charter boats did not have engines, and others lost theirs in rather amusing ways. One lost his engine when the skipper told his crew to drain the oil and change it, which the young man did. Next time the engine was started, it ran for a few minutes, then seized up solid. It turned out the crew, straight from a native schooner, had filled the engine with the only oil he had ever seen, linseed oil.

My own boat Iolaire also lost her engine in a rather amusing fashion. Bob Cryster had purchased her shortly after her arrival in the islands from the Canaries. Her engine did not work and was rather ancient, so he sent her down to St. Lucia to have the engine overhauled. After much money had been spent, the engine was again working and they decided to go out for a trial run. The crew dropped the mooring and the engine was put in gear, but nothing happened; the shaft was turning but the boat was not moving. Deciding that the prop must be fouled by so much inaction a crewman put on a face mask and dived for a look. It is said that the curse words were heard coming out of the air bubbles, and he came up to report that, after all that expense to fix the engine, the “trouble” was that both blades of the folding prop had fallen off while she was crossing the Atlantic. Cryster was so frustrated that he ordered the engine dropped overboard and used as a mooring. For all I know it is still used that way in St. Lucia today.

When I purchased Iolaire she still had no engine, but she did have the world’s noisiest generator, which resulted in another story. We were sailing back from St. John, the wind was light, it was getting late and one of the charter parties suggested that I start the engine. I decided that if they could not tell the difference between and engine and a generator I might be able to fool them. I went below, started the generator and fiddled with the carburetor until it was running its noisiest, and then went on deck and pointed out to everyone that since it was a very small engine we had better keep the sails up.

We spent the afternoon carefully trimming sails and catching every puff, finally reaching St. Thomas harbor just before sunset. As we rounded West Indian Company dock and came on the wind, we discovered we had enough wind to sail quite nicely, so I suggested that we cut the engine, be sporting, and sail alongside the dock. As we secured everything and the charter party began to leave, they all thanked me for a pleasant day and one said, “It certainly was good that you had that engine, or we would never have made it back before dark.” My charter-skipper friends standing on the dock had very quizzical expressions on their faces, but no one let the cat out of the bag and there were many laughs later.

Donald M. Street Jr. has spent his life cruising, charting and writing about sailing. Street explored the Caribbean for 45 years aboard Iolaire, his 46-foot engineless yawl. He sailed her across the Atlantic seven times and up the Thames to London 12 times. Now 80, he sailed the Caribbean aboard L’il Iolaire, a 28-foot yawl that was also engineless, until a catamaran dragged her down during Hurricane Ivan. For more on Street’s life and work visit www.street-iolaire.com.