This fall, when you shop the electronics booths at the boat shows, expect the sales pitch to lean on networking one manufacturer’s radar, GPS plotter, sonar/fishfinder, autopilot, weather sensors and even ship’s video monitoring via a proprietary system.

“It’s the complete solution for a boat-main unit with a bunch of sensors,” said Dave Church, vice president of marketing at Si-Tex.

Weaving a basketful of navigational aids into a single sales package may seem complex, but in reality, it simplifies the electronics suite and (manufacturers hope) the customer’s decision-making process.

The advance that led to this moment, when manufacturers can pitch you a complete $7,500 to $10,000 system instead of single components ranging in price from $1,200 to $3,000 apiece, is just one kind of technology-broadband.

BROADBAND AND BOATING

Broadband technology has been in the mainstream of the computer industry for about 20 years. Anyone who has a DSL connection to the Internet has been using it. Only during the past five years or so has it become common in marine electronics.

Flowing data from one device to another used to be simple. The protocols developed in conjunction with the National Marine Electronics Manufacturer’s Association-0180 and 0183-are more than up to the task of carrying position or wind-direction data to the autopilot, for example. These protocols are the same as the computer industry’s RS232, and they permit data to flow like cold molasses at only 4,800 baud. The new NMEA 2000 protocol, though 20 times faster than 0183, still can’t transmit graphics.

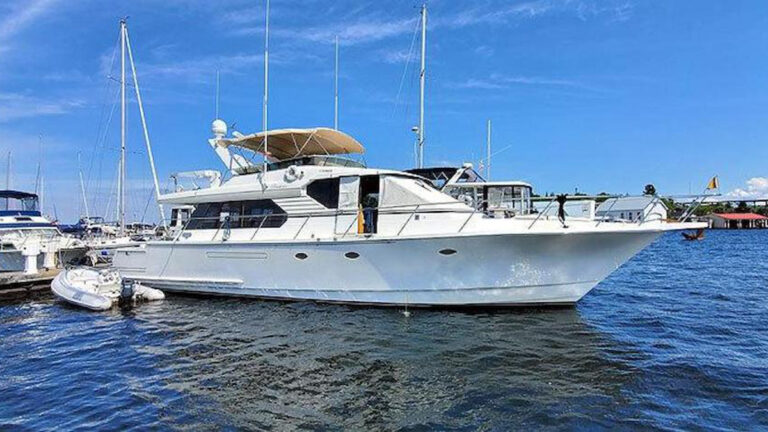

A typical NMEA-standard electronics suite aboard a 60-foot yacht contained a GPS-with or without a plotter-radar, an autopilot and a fishfinder/sonar. Each was its own computer, able to stand alone, and each had a dedicated display. What’s more, each device had to be hardwired to the boat’s DC electrical system. Placing all of these displays within easy sight lines of the helmsman and navigator crowded the nav station or the dashboard. Hardwiring created complex and heavy wiring runs, which also increased the potential for short circuits.

The industry’s switch to broadband, or broad spectrum, lets engineers increase the volume of data transferred among a yacht’s devices without dramatically increasing the speed of the central processing unit. It “widens the pipe.

In marine electronics, broadband functions exactly like the local area network (LAN) at your office. Individual components in the network, daisy chained together as in the Raymarine hsb2 ARCnet-based high-speed bus system or linked through a hub as in Furuno’s Ethernet-based NavNet system, selectively take data from the bandwidth. They are able to do this because the instructions for the processor and the data are stored separately. In a system of limited bandwidth, data and instructions are stored together, which has the potential to create a lot of errors. Broadband transmits a lot of data at very high speeds (2 to 3 megabits per second for a radar image) and with few errors.

A SIMPLE SOLUTION

Exactly why the marine electronics industry evolved toward proprietary networking systems remains speculative. Did customers demand more speed combined with simplicity of operation, or did the R&D folks simply think the time for broadband had arrived? Some of each no doubt spurred the development, and so did the desire of boatbuilders to simplify installations and give their stylists some latitude in the design of helms and nav stations.

Anyone with an ounce of foresight could have predicted the attraction of these networks. One display, a single CPU and a handful of sensors communicating with one another over a broadband bus simplifies installation, reduces the number of prospective trouble spots and gives the user the speed and convenience of menu-driven operation. Si-Tex’s Genesis is such a system. Brian Vlad at Simrad’s Dania, Florida, office called this the imbedded approach and said a system of separate black boxes (as are PCs on a LAN) gives the same results.

In all of the networks on the market, increasing the diameter of the “pipe proved to be a lot less expensive than increasing the pressure (speed) of the data-flow through it. This is key for the marine electronics market, which, compared with the broader computer market, is a pinhead speck on an elephant’s backside. The relatively small volume of units sold in the marine market forces manufacturers to develop new products around tried and true technology and off-the-shelf components. This prevents the cost of production from ending up in the stratosphere.

Also, development of new products in the computer industry far outruns that in marine electronics. The public seems perfectly content with the rapid obsolescence of computers-sometimes within a few months-but the marine industry looks for a product life of four to five years. This used to be eight to 10 years, but electronics-savvy boat owners seem to have forced a reduction.

That’s just fine by marine electronics engineers, who would rather focus on dedicated products within a networking system. A dedicated autopilot, for example, does not need the broad capabilities or computing power of a typical PC.

“You’re not going to run an Excel spreadsheet on these systems,” said Raymarine’s Keith Wansley.

“Dedicated products,” Wansley said, “are faster and better than a PC”. The reason: Engineers can design each microprocessor to perform a relatively narrow range of tasks, specialists, if you will. This prevents the marine systems from having a bottleneck of data, which can occur on a medium-speed PC. Vlad referred to these dedicated processors as application-specific.

YOUR HELM’S FUTURE

Everyone agrees that networking is here to stay. The movement began about 20 years ago with hardwiring individual components into a system that communicated via a 4,800-baud protocol. Broadband technology, on the scene and growing in force during the past 10 years, allows a network’s components to speak to one another with lightning speed.

These networked systems will be tough to resist if you’re the kind of person who long ago dumped the dial-up for a DSL. On the other hand, if you work in one of the growing number of offices that has already moved to wireless LANs, you may want to wait a while. Marine applications can’t be all that far behind.

By the time your five-year itch for new electronics kicks in, the boat show booths should be abuzz with chatter about wireless networking systems. Stay tuned.