At 33 feet below the ocean’s surface, the human body is neutrally buoyant — essentially weightless. Above that, the gases in your body naturally make you float upward. Below it, the atmospheric pressure compresses those gases, and you sink at a rate that increases with your depth. Divers call this phenomenon “the doorway to the deep.”

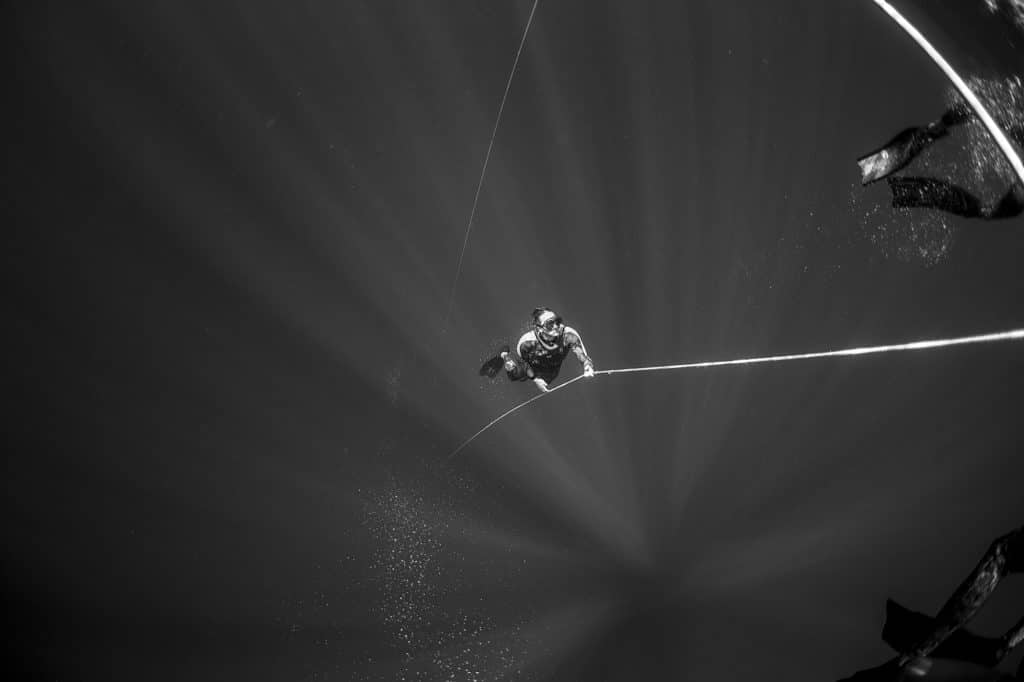

Thirty-three feet down is exactly where I found myself recently, floating statically, swaddled in 2,000 feet of warm Atlantic Ocean in the Bahamas, with only the air in my lungs to sustain me. When I looked up, I saw strands of gauzy light reaching toward the water’s surface, where a roaring Bahamian sun silhouetted my fellow divers and the Pursuit S 408, the vessel that had brought me to this strange space. When I looked down, all I could see was dark-blue nothingness. Back in college, I would often begin term papers with a favorite quote from Friedrich Nietzsche: “If you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” Back then I was grasping at wisdom I didn’t quite understand, in an attempt to pad my intellectual credibility. But in that moment, down below, as I floated Zen-like in a boundless expanse, fully mortal in an immortal place, I finally understood what the great thinker meant. So I bent at the hips, flipped my fins over my head and kicked downward, feeling the sea’s gaping maw suck me in.

Don’t worry guys, I lived to tell the tale.

The plan for this story was hatched nearly two years earlier, over beers in a West Palm Beach bar with Pursuit’s in-house photographer, Marc Montocchio. He is a former South African Navy underwater demolition diver — both a serious waterman and a bit of a hell-raiser. When I told him I wanted to do a free-diving and spearfishing expedition with Pursuit, he was all over it. Pursuit’s marketing director, David Glenn, who is a waterman himself and has a family with some serious aquatic bona fides, including three sons who have surfed professionally and a wife who is a former pro water-skier, also loved the idea.

It seemed like everything was in motion. But then, as it has a habit of doing, life happened. We didn’t have quite the right boat. We had difficulty finding an instructor. I changed jobs. A year dragged on, then another. The story moved along like all the important things in life seem to do — that is, at a glacial pace, and then all at once. Pursuit launched the S 408, a versatile, monster-size center console built for fun and adventure. We came into contact with Errol Putigna, one of the world’s foremost freediving instructors. And I found myself desperately trying to remember my high-school Spanish as I directed a cabdriver from Palm Beach International Airport to a marina in Fort Pierce, Florida, where the S 408 was docked. Allá derecha! Allá derecha! That was pretty much all I could recall, but somehow, we found the boat anyway.

Once on board, I inspected the vessel and found it well-suited to our needs. In ward-opening dive door? Check. Triple 350 hp Yamaha outboards to power our journey across the Gulf Stream to Spanish Cay in the Abacos? Yup. And the stowage — which can be a concern on other center consoles — made the loading process feel like we were packing a clown car. Because Spanish Cay is so remote (it’s essentially a marina and an airstrip), we needed a lot of food. Bags and bags of groceries were marched out of the car in endless fashion, and things seemed like they might be getting dire until I poked around up front and found a huge, and heretofore unutilized, stowage area beneath the forward sun pad. Finished packing and fully loaded, we were soon on our way to Spanish Cay, a six-hour poke that would prove to be quite eventful.

When we left Florida, there was an intermittent drizzle, but by the time we reached open water, we were plowing through full-blown squall lines at a 30-knot cruise. Angry-looking clouds pelted us with a hard rain, and the winds whipped the sea into a stubborn chop. Yet the 408’s hull delivered a smooth and secure ride. Yeah, we all got a little wet — drenched, actually — but communing with the elements is part of the fun on an open boat. So I sat on the aft-facing bench seat behind the console, hunkered down in my windbreaker, and commune I did.

After a few hours, the weather repented, and Glenn steered toward a plane wreck about halfway between Grand Bahama and the Abacos. He and I had spearfished and snorkeled this wreck a few years back, and we knew the others would appreciate it. Hopping in the water here would delay our journey by an hour or so, but we were already wet, and plane wrecks are really cool to see. We suited up with snorkeling gear and jumped in.

The last time I dived on this spot, I flopped overboard and landed smack in the middle of a veritable army of midsize barracuda, hundreds of them, all facing the same direction and stock still in the dim-lit gloom. It’s a hard image to shake. This time, there were no barracuda, just a few over-entitled lionfish floating lazily near a turbine, and a lone nurse shark curled under a wing like a cat. The water was about 25 feet deep. We all held our breath and dived, dived and dived again. Putigna patrolled the surface, breathing through his snorkel, getting a feel for his pupils’ level of comfort in the water. After about an hour, we all crawled back in through the dive door and made the final push to Spanish Cay.

We pulled up to the dock just before dark and made our way to the Point House restaurant (the only one on the island) for dinner. We discussed the next day’s freediving plans over grouper sandwiches and cold Kaliks. After dinner I walked along the dock through the ink-black tropical air toward my condo, anticipating the next day’s dive. Then I passed a sport-fisher with its underwater LED lights on, creating an orb of eerie purple around the hull. I looked into the water, and an unmistakable silhouette glided silently from under the dock: a wedge-shaped, 9-foot wraith. This was no nurse shark. This one was a serious beast, the kind with teeth. I pegged it as a bull or possibly a lemon. Then another shark the same size swam up alongside it. A third appeared at the light’s perimeter and swam at them headfirst. It was pure nightmare fuel. I’d like to say I slept easily that night, but in truth, those sharks slid through my dreams as easily as they had slid through that dark water.

The next day broke bright and hot, as they tend to do in the Bahamas. After breakfast, Putigna pertly handed out reading materials and explained that, as with scuba diving, the classroom session was an enormous part of becoming freediving certified. Putigna is one of those people you meet and think, that guy’s a teacher. Which he is. He teaches high-school foreign languages for his day job. (I could have used him in that cab.)

He started with the basics. Literally, Putigna taught us how to breathe. Deeply, slowly and from the belly, where the tiny sacs in the lungs known as alveoli are plentiful. As it turns out, when it comes to breathing, most of us are doing it wrong. We only use the top half of our lungs, up in our chest, and miss out on the full benefits of our physiology. Buddha was onto something. For maximum oxygenation, you need to breathe from your gut.

We also worked on meditative techniques. When free-diving, you want to get your pulse as low as possible, since every heartbeat sucks up valuable oxygen. Even thinking uses oxygen. Top freedivers have been recorded with heartbeats as low as seven beats per minute — significantly lower than coma patients. A heartbeat that low won’t sustain human consciousness on land, but at depth, it does. Your body changes once it’s deep underwater, reverting to an almost prehistoric state. All humans have the mammalian diving reflex, which makes our heart rate drop by about 25 percent the moment our faces submerge in cold water. It’s an evolutionary link stretching back to dolphins, whales and seals. Things are, quite simply, different under the sea.

Putigna also focused on safety, safety, safety. The first rule of freediving is always to dive with a buddy. Almost no one drowns at depth. Your body won’t allow it; instinct makes you swim to the surface. And that’s where people drown, usually within 15 feet or less of the air they so desperately need. Thus, a trained spotter needs to be at the surface to help you in an emergency.

Because if you’re not cautious, this sport can turn deadly, instantly. Putigna told the cautionary tale of Patrick Musimu, a legendary Belgian freediver who could hold his breath for eight and a half minutes and once freedived to an unthinkable depth of 685 feet. In 2011, he drowned at age 40 while training alone in his family’s pool. It doesn’t matter who you are. Safety comes first.

That afternoon, we piled back onto the S 408 and popped over to a nearby marine park to put our classroom skills to the test. We kicked our way through the pristine waters, over brilliant ribs of coral that were too close to the surface for even the boat, which draws only 2 feet 11 inches, to follow. We found a depression in the coral that led to a sandy bottom at 40 feet deep, a perfect spot to practice our safety techniques among sea turtles, bright reef fish and baby barracuda.

Soon the sun began to sink and it was time to head back, but we had been caught in a current the whole time without paying it much heed. When we looked up, the boat was a good mile away. The distance wasn’t a problem for our group, as we were all strong swimmers. But here’s what the problem was for me: I used to swim competitively, so I can move pretty fast in the water, and I ended up well ahead of the pack. Now the thing about reefs is that as the sun goes down, the light gets lower and lower, and all those cute little critters get bigger and bigger. The transition is awesome when you’re talking about sea turtles, but less so when a barracuda the size of a snowboard zips up out of nowhere and stares you square in the eye from a yard away. This thing had teeth like my sister’s German shepherd. I decided it might be a good idea to tread water and wait for the group.

The next morning, we were floating above the aforementioned 2,000-foot abyss. Though the water was choppy, the relatively beamy (13 feet even) S 408 made for a stable staging area, despite a knifelike hull that has 20 degrees of deadrise at the transom. Putigna swam out first and dropped a 70-foot line with a weight on one end and a float on the other. From the surface, we could barely make out the weight in the murk. Now, we were going to work on diving to depth. Real depth.

Here’s what people don’t realize about freediving: Holding your breath isn’t the hard part. The breathing techniques we’d learned work incredibly well, to the point that a beginner can learn to hold his breath for two, three or even four minutes within days. The hard part, at least for me, was equalizing the pressure in my ears. Freedivers need to “clear” — hold the nose and blow out — constantly and rapidly as they dive down. I learned this lesson the hard way. On my final dive that morning, I got within 10 feet of that 70-foot-deep weight. I got excited. I forgot to clear. And suddenly, it felt like someone had stuck a power drill in my ear canal. Sixty-five feet below the surface, I was experiencing blinding, panic-inducing pain. I struggled to right myself and shot toward daylight, the pain dissipating as I rose. When I breached, Putigna was there waiting. “You forgot to equalize, didn’t you? Don’t do that! You’ll blow out your eardrums!” Treading water in the middle of the ocean, I could only nod my head. But thankfully, I heard him loud and clear.

Our final day in the Abacos was all about spearfishing, the most ecologically sound way to catch a fish — not to mention the most primal. When you spearfish, you’re not sitting on a plush mezzanine, drinking a beer and watching baits skip behind you. The sport is physically taxing, an intense anaerobic workout in the truest sense of the word. And if you’re lucky enough to spot a fish, dive down and spear it, that fish still isn’t your fish until you get it back to the boat. Those familiar shapes, the ones I saw gliding under the dock on the first night, they’re here as well. And you’re in their house, taking their food away from them, and they’re not too sure how they feel about that.

When spearfishing, sharks are nearly omnipresent. Most species hunt using electromagnetic sensors in their noses. They’re not attracted to blood, as is the myth. Instead, sharks are attracted to the vibration a dying fish makes as it wriggles around after a spear pierces it. (That’s part of the reason you want to “stone” the fish. That is, aim for its brain, which kills it immediately. No wriggles. No vibration. No nothing. The fish simply morphs from animal to dinner in less than a second.)

Even wilder about the sharks is that you probably won’t see them until the moment they’re on top of you. But they’re always out there, lurking in the crepuscular deep, just beyond your field of vision. And they can see you. And damn those things are fast. I’m told that, with time, sharks become just another part of the experience. But, like many aspects of this comfort-zone-busting sport, having a reef shark brush over your shoulder when there’s blood in the water is going to take some real getting used to.

The only apex predators we encountered were reef sharks when we were in the water, but a few weeks after we finished our trip, off a cay nearby from where we were, a dentist from Texas was bringing a speared hogfish back to his boat when a bull shark bit him in the face. Luckily, he survived without major injury. But despite such horror stories, attacks are incredibly rare. The animals are a part of the sport. It may sound crazy to the uninitiated, but for some spearfishermen, I suspect that being in the water with large predators is all the more thrilling.

Shark-bite-free, we speared a menagerie of fish — hogfish, cubera and mutton snapper, grouper, triggerfish, even mackerel — and by the end of the day, we were all bone-tired. Back aboard the Pursuit, I saw smiles on every face as we peeled off our wetsuits. It would be a 20-minute trip back to the marina, where the cooks at Point House would fry up our catch.

I made my way up to the forward lounge seating as the engines fired up. Then we took off screaming back to our base camp at 40 knots. The warm sun dazzled overhead. The sky was a torn-up denim. I laid back in my seat, closed my eyes and let all the air in the world wash over me.