yachting/images/magazine/2006/042006/fea_russia2_525x279.jpg

I first encountered the word “Kamchatka” on the board game Risk when I was a child. It was that strategic, most eastern part of what was then called the U.S.S.R., a long peninsula that we all wanted to capture.

I later came across Kamchatka when reading about shamans and their practices. In his book Alaska, James Michener writes of the terrible struggle between the Aleutian Indians and the Russians in Kamchatka who sought to press the Indians into service. It was the shaman-led Indians against the Empire. The Empire prevailed.

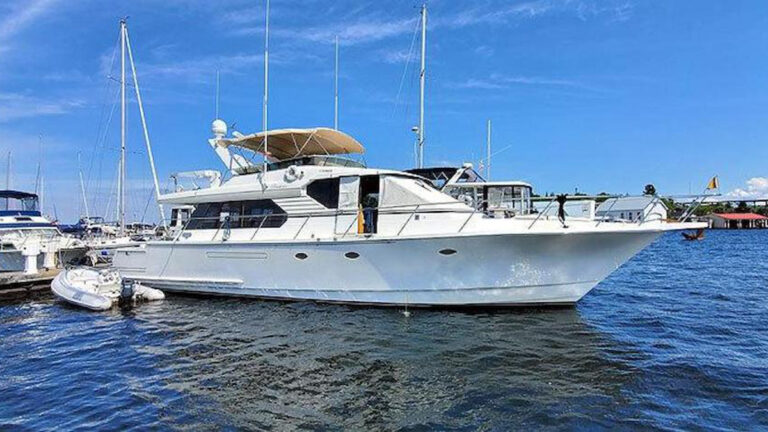

Now, I wanted Shaman to prevail. The shaman is the conduit between the people and the spirit world. And so this boat was to me. I built Shaman, an 88-foot sloop, in 1997 to explore remote parts of the world. I envisioned her as a sanctuary where those I loved could be invigorated by contact with the wildest and most powerful parts of the planet, and then return, strengthened, to the challenges of life. We had taken Shaman to South Georgia and Antarctica (featured in Yachting, October 2004), Spitzbergen and the Galapagos. Now, it was time to head to Kamchatka.

Beyond the Bering Sea

Kamchatka is not a place one might pick for a cruising ground. The winds and waves of the Bering Sea are notorious. The broken economy of eastern Russia suggested that we should expect to be self-sufficient. In preparation, Shaman spent the winter of 2004/05 in the yard. We sailed Shaman north from Seattle and then to the Aleutians. But it wasn’t until we left Attu, the westernmost point in the U.S., that I realized the gravity of the conditions here in the cold stormy seas.

Attu, the last of the Aleutians, is only 580 miles from Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy (PK), our check-in point in Kamchatka. But to get there, we had to cross shallows formed by an ocean ridge that generated some of the most turbulent and chaotic seas that Shaman has ever traversed. We slogged toward PK in huge waves and 25- to 35-knot headwinds. In the midst of the storm we passed the Komandorskiy (Commander) Islands where the great nautical explorer Vitus Bering is buried. But until we cleared into Russia, we were not allowed to duck into these islands. We got our first glimpse of Kamchatka when we were still almost 50 miles away. Enormous glacier-capped peaks rose on the horizon, some of the peninsula’s 150 volcanoes.

I had been warned by the folks at Waypoint Marine, who organized our trip, that clearing in at PK, the main city in the region, was no picnic. It was still under the control of central Russia, some 3,000 miles away, despite the disbanding of the U.S.S.R. and all the republics between.

PK serves as a military base and upon arrival, after battling head seas and cold for 56 hours, we were told to sit outside the harbor. We circled and waited. Once, we were told to come in, then ordered to reverse course. After a few hours of being told that our papers were not in proper order we were finally allowed to dock. At that time we met Martha Madsen, our liaison, who helped us to arrange “permissions” to visit harbors along the coast. She runs a business called Explore Kamchatka that is essential for making any kind of headway here. Bureaucratic resistance was a constant source of delay and frustration. Yet we had to remember that such obstacles, whether they are made by mankind or by Mother Nature, are barriers that keep what is behind them protected and unusual and interesting.

A Salute to Lenin

PK’s harbor was full of ships, many abandoned or in disrepair. It was our first glimpse of the consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union. With the remnants of military control in place, Adam Smith’s invisible hand of the market was precisely that: invisible.

Once checked in, we had a chance to explore the dilapidated city by car. As luck would have it, when we reached the Lenin statue on the edge of town we were treated to a military dress parade. I could not help but notice the comedic poses being struck by the soldiers. Their faces betrayed a sense of the absurd, as if they were wondering why they were performing this ritual.

Leaving PK was just as difficult as arriving. After working two days to get water, fuel and food, we appealed to the government officials to set us free. Hoping for a 2 p.m. departure time, we made calls in the morning to get the customs process started, even though we were only moving to another anchorage along the coast. By 7 p.m. we were finally allowed out of the harbor, but the approach of a cold front with winds from the NNW at 50 knots convinced us to turn back. The dread of reentering the harbor was somewhat alleviated when two of our Russian- speaking crew were able to negotiate for us to stay at anchor and leave the next morning without returning to the dock. We slept well, having preserved our freedom, but awoke to learn that we were again to be held until 2 p.m. because of an impending entrance of a submarine.

We made the best of a sunny morning, watched an older diesel submarine maneuver around the harbor and then, in much calmer seas, set sail for the Komandorskiy Islands, a nature preserve known for tremendous bird and animal life. As we sailed along the coast we saw thousands of puffin and cormorant swarming the cliffs.

The next morning the sun shone as we rounded the tip of one of the islands and headed toward the backside and Vitus Bering’s grave, which our captain, Jon Whitley, correctly identified from using the British Admiralty Pilot. The waters were very shallow and a beautiful valley opened up before us as we took the dinghy toward the beach. Ashore we found a stream that was filled with several hundred salmon.

We hiked about a quarter of a mile up into the valley and on a hillside came across a large black iron cross and a series of graves, a beautiful serene sight looking down the valley and out to the sea. Bering and his crew had been in the process of repairing their boat when they perished here.

Cruising with a Shaman

The next day we sailed nearly 200 miles north up the volcano-rimmed coast to the town of Ossora. Here, too, many buildings were abandoned-only the KGB building was new and shiny. The population of about 6,000 was less than half of what it had been 15 years before. Villagers said that the big Russian fishing companies now had all the licenses and that locals were very restricted in what they could catch for their own subsistence. In practice, though, it appeared to me that the local people were quite free to do what they wanted. They seemed to have befriended the military and KGB and collaborated so they could piece together a humane existence.

Here, and in other coastal towns, fresh produce was in short supply. Gasoline for the tender could not be found. It took three days for a charter flight with supplies to make it through. Waiting by the airport, we had our fill of vodka. Finally, the supplies arrived and we set sail to Korf about 130 miles north in search of the Koryak people and a shaman, a woman said to be in her late 90s, who goes by the name of Moolynaut. In appearance, the Koryak look akin to American Eskimos and make their way through life hunting, fishing and herding reindeer. There is still great reverence in Russia for the spiritual powers of these people, and in the lore of the Siberian Eskimo and the Koryak the female shaman is the most powerful of all.

We learned about Moolynaut and her family and many details about the region thanks to one of our Russian crew, who had met the American explorer Jon Turk during his voyage here. In 1999, Turk kayaked from Japan along the Russian coast and then crossed the Bering Sea seeking to retrace the route that he believed primitive man had taken to reach the North American continent.

In his book about the journey, In the Wake of the Jomon, Turk tells of how he did a head-over-heels landing along the beach in a town called Vyvenka and a couple of fellows named Oleg and Sergei came to pull him out of the water and to safety. In Korf, we found Sergei and he guided us back to Vyvenka, 20 miles southwest to meet Jon Turks’ family of friends.

Oleg was out fishing, but we met his wife Lydia, a vital and radiant woman who spoke English, Russian and Koryak. She greeted us with great enthusiasm and introduced us to several generations of family, including Moolynaut, the shaman. This elder woman, who was no taller than four feet, eight inches, had a penetrating gaze and an amazing awareness of what was happening around her. Her capacity to observe and her constant alertness were striking.

Lydia invited us to join the family at their fishing camp the following day. We took the tender several miles upriver and joined an amazing feast of salmon and pork barbecued along the riverbank. A large cloth was spread on the ground and we spent hours eating, arm wrestling and telling stories. From these lovely people we learned of their history and how Lydia’s father had been a powerful reindeer herder before the government appropriated his herd. We heard how they still fished and hunted to provide for the winters.

The following day we took about 20 of Lydia’s extended family out for a sail aboard Shaman. All ages were able to steer, trim sails and climb up in the Park Avenue boom for a rest or head below for movies and music. It was a delightful experience, and what was most striking was the simple exuberance of all ages from 3 to 97, four generations of family together in support of one another. Their self-assured behavior on land and at sea conveyed a deep confidence. Laughter was ever present; these people were simple, together and joyous. Perhaps it was Moolynaut who had brought the spirits into line for her family.

Into the Wild Lands

We left Vyvenka and our friends the next day and moved again to the north and east, past Cape Govena and into a series of bays with abandoned fishing villages, their structures forming ghost towns.

Here in these more remote regions, we began to see frequent signs of bears as we roamed on the beach. Unlike Alaskan grizzlies, these bears were much more cautious regarding the animal called man. It appears that poachers are quite active in this part of the world and the bears do not have the protection given to their American counterparts. Sailing along Cape Govena at dusk we saw shipwrecks near the beach-and then a grizzly, illuminated by the golden sunset. As we approached the beach by tender, we watched him climb the sheer of a cliff. It was fantastic to see the bear, weighing more than 500 pounds, scale that cliff in about 90 seconds. It was a climb, if I could do it at all, that would have taken me more than two hours.

We also encountered bears when Erik Soper, a Whitbread Race veteran and one of our crew, was fly-fishing from a dinghy. The bears swam across the river to be on the shore near the salmon. As we returned from bird watching one day, we came down to the river and saw Erik casting for salmon with bears standing on the beach 20 feet behind him. I never did ask how he would have cleared a back cast into the brush had he snagged a tree.

By now, we had cruised more than 700 miles north of PK and it was time to head back. We sailed all night and at dawn we came to an island full of sea lions on the rocks. As the sun rose, a beautiful red sky and golden hues silhouetted these majestic creatures.

We proceeded south and came to the Zhupanova River where we enlisted guides to take us up the river to the Kronotskiy Reserve. Here we saw the awesome Steller’s sea eagle-in fact, we saw dozens of these rare yellow-beaked birds with eight- to nine-foot wingspans-much larger and more powerful than the bald eagles in the U.S. We watched as they performed a brilliant exhibition, their wingspans painted against the sky with snow-covered volcanoes in the distance.

On our second to last day, we sailed all day and, near Shipunskiy Point, came upon a pod of what must have been nearly 100 feeding killer whales. In awe of their power, we sailed in and out among them as they thrashed about for fish. Here, so far from the support of civilization and captivated by the sights of Mother Nature, a sense of magic descended upon us like a shaman’s spell. I had felt it while hiking, beachcombing, watching the bears and the eagles-a clear sense of beauty and appreciation that washed through my soul.

These were moments that would become memories, and memories that would suggest future possibilities. These are the times that we yearn for when we return home. The anticipation of fellowship and the magical beauty of nature is what often makes difficult times bearable and infuses us with the stamina and perseverance to go on, if only to be able to taste this magical potion again.

When the whales moved on so did we. Shaman sailed on through the night, with a beautiful full moon to guide our return to PK and the conclusion our voyage.