EVERYTHING WAS PERFECT…

The competition was safely astern. A fresh 25-knot breeze was piping over the port quarter, and Mar Mostro – Puma Ocean Racing’s entrant in the 2011-12 Volvo Ocean Race – was smoking along under a full sail from Alicante, Spain (and the race’s start) to Cape Town, South Africa. Skipper Ken Read had just come off watch when his ears were jarred. Bang! The noise sang out from the rig. Mar Mostro stood up on her lines as boat speed plummeted from 23 knots to zero. “The mast is down! The mast is down!” shouted crew member Ryan Godfrey from the cockpit. The sailors could barely react before the stopwatch to salvage their race campaign, and perhaps much more, stared.

Boaters in the 21st century live in a world that makes 1990 seem like it was 125 years ago. We have round-the-clock satellite communication, EPIRB-signal monitoring and — at least in U.S. waters — world-class rescue services. While this technology provides a wider safety net, the only way to ensure real safety and sustainability at sea is with know-how and a combination of new and well-tested safety gear. That’s what immediately came into play for the crew of Mar Mostro.

Despite their predicament, Read and company never relinquished their passion to finish the race, one they’d devoted five years to attempting. That kind of resolve might have been their greatest asset as they pressed on toward Cape Town. They also had assistance at hand, literally.

“It was kind of weird,” Read says. “Because the first thing we did was get on the phone.”

Thirty years ago, Read and his crew would have had to use single-sideband radio. But in this case they were the beneficiaries of satellite communication technologies that allowed them to make instant contact with shore support from deep in the south Atlantic Ocean.

Telephones lit up on multiple coasts. Puma Ocean Racing’s shore team received a call in Newport, Rhode Island. So did Volvo Ocean Race officials in Spain and Berg Propulsion (a sponsor) in Gothenburg, Sweden. Family and friends of the multinational crew were alerted too. International maritime traffic sprang into action. Sourcing diesel was Read’s primary concern since Mar Mostro required fuel to power everything from the satcom to the watermaker. Read’s crew had only 36 to 48 hours worth of diesel remaining.

Here the team was, 660 miles from the nearest speck of land: Tristan da Cunha (population: 275), the world’s most remote inhabited archipelago, where supplies arrive via cargo ship four times a year.

But the wheels were in motion. The team’s backup rig, which was in Rhode Island, began its 747-aided migration to Cape Town. After consulting with race officials, the team issued a pan-pan. The captain of a Russian-flagged cargo ship received the message and diverted his vessel 100 miles to transfer 1,000 liters of diesel to the stricken race boat. The fuel arrived 18 hours after Read’s initial call, kindling a glimmer of hope.

“One of the scariest moments,” Read says, “was being tied up next to this massive steel building, in our little carbon-fiber boat, in the middle of the ocean, trying to get fuel aboard — via rope — from 200 feet in the air.”

Two and a half days later, the team was welcomed on Tristan da Cunha, where it remained for five days. A ship was dispatched from Durban, South Africa, and upon its arrival, Read watched in suspense as Mar Mostro was hoisted onto the cargo deck and lowered into her cradle, the crew syncopating their moves with the 6-foot swell.

The team spent five days en route to Cape Town scrutinizing its broken rig.

“The weak link was a hanger pin that held a port shroud,” Read says. “It was always going to end in tears.”

Miraculously, the team arrived in Cape Town in time for the in-port racing and the start of the race’s second leg. It eventually made history by reaching the podium (third, overall) seven months later, despite not having finished the first offshore leg under sail. Had it not been for the team’s satellite communication system, there’s no telling how it might have ended for the Mar Mostro crew.

The Troubleshooter

Tim Kent had every reason to feel confident. He and co-skipper Rick McKenna were settling into a fast night of close-reaching, 110 miles north of Bermuda in 25 to 30 knots of air. Even better, professional oceanographer Jenifer Clark predicted that a favorable Gulf Stream eddy would give a boost to Everest Horizontal, Kent’s Jim Antrim-designed Open 50, during the first night of the 2003 Bermuda One-Two, en route to Newport, Rhode Island.

Two months earlier, Kent and the boat had completed the Around Alone solo circumnavigation race. While Everest Horizontal had suffered a hard grounding during a tow into Tauranga, New Zealand, the boat had fared fine all the way home. Now they were moving with ease, and with Clark’s encouraging report still in hand.

Until … boom!

Everest Horizontal rounded up, and Kent instinctively moved to the autopilot. No such luck. A glance over the side revealed the keel strut unburdened of its 4,200-pound keel bulb. The boat no longer had ballast. Within 90 seconds it capsized. Kent grabbed the ditch bag containing the boat’s SOLAS flares. McKenna reached for the EPIRB and handheld VHF radio. They were now in the ocean.

“It was rough, and blowing hard,” Kent recalls.

They clambered aboard the slippery, upturned hull, each man clinging to a rudder. Just as the true severity of their predicament registered, a large figure loomed on the horizon: a Royal Caribbean cruise ship. Using his waterproof headlamp — a piece of mission-critical gear, says Kent — to read the instructions, Kent loosed a flare to attract attention. He quickly followed this with a volley of additional flares, which punctuated the night sky.

“By the time I fired off the second flare, the ship had already turned toward us,” Kent says. About 90 minutes later, Kent was aboard the Nordic Express, surprised to find that the captain employed the same Jenifer Clark-produced Gulf Stream analysis that he had been using. Kent’s next call was to a still-sleepy-eyed Clark to thank her for saving his life: If her analysis hadn’t directed all actors to the same stage corner, the end result would have been far more serious.

Kent says grabbing the safety flares was the smartest thing he and McKenna did before going swimming. “It never occurred to me that I’d need to be rescued at sea. But if you do, a Royal Caribbean cruise ship is a nice place to wind up.”

The Rescue Man

Gabe Pulliam is one of a kind. Make that one of 370. That’s how many U.S. Coast Guard rescue swimmers there are, which is why he gets called into the most dire situations — like the one involving an injured sailor 45 miles off Big Sur, California, not long ago.

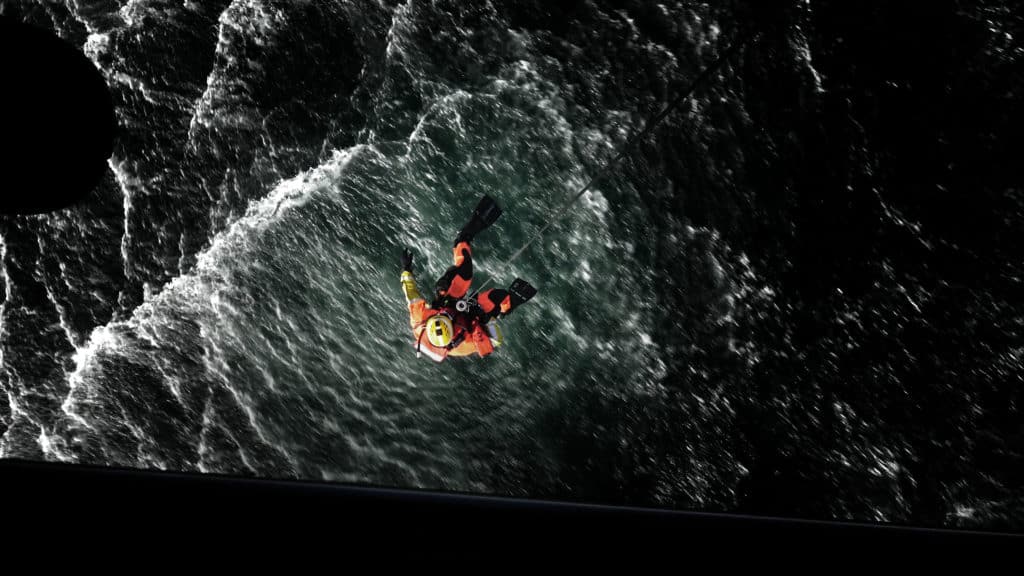

On that night, a thick fog conspired against Pulliam and his team of two pilots and one flight mechanic. Their helicopter’s fuel was low. Visibility was horrible. Seas of 15 feet complicated matters.

U.S. Coast Guard procedures dictate that Pulliam either jump from the helicopter or be lowered into the water near the sailboat and swim to it, but the inky darkness and the sailboat’s wildly rocking mast rendered plans A and B unworkable. Instead, the team would lower Pulliam into the water near a waiting Coast Guard rescue vessel, which would transport him to the sailboat. Pulliam shook off the punishing hours from the helicopter ride (Coast Guard helicopters aren’t exactly Boeing 787 Dreamliners), donned his fins and rode a cable into the storm-tossed seas.

“The sailor had hit his head and couldn’t answer my questions,” Pulliam said. Two factors limited his options: the severity of the man’s injuries and the helicopter’s dwindling fuel. Pulliam radioed the copter and advised that he and the patient would enter the water together and would ride tandem in the basket — a dangerous but time-effective maneuver.

“We typically don’t do this,” said Pulliam, who has served as a rescue swimmer for 15 years, “but I needed to help him medically as quickly as possible.”

The mission was successful, but Pulliam and his crew mates weren’t finished. After a long flight back to base, they still had to wash down the entire helicopter — saltwater corrosion is yet another risk.

“Eighty-five percent of our time is spent maintaining equipment,” Pulliam explained. “It’s not Hollywood.”

Then, and only then, did the team rest.